China’s Grey Future? How the Demographic Shift Affects the PRC

A discussion with students at Leiden University and Rotterdam’s School of Management

Over the past decades, China has seen a marked demographic shift. Due to the one-child policy, the number of people who are dependent on the family income has decreased compared to the number of people who work to produce that income. Economists like Wei and Hao (2010) have estimated that this “demographic dividend” may have accounted for up to a sixth of China’s economic growth during the 1990s.

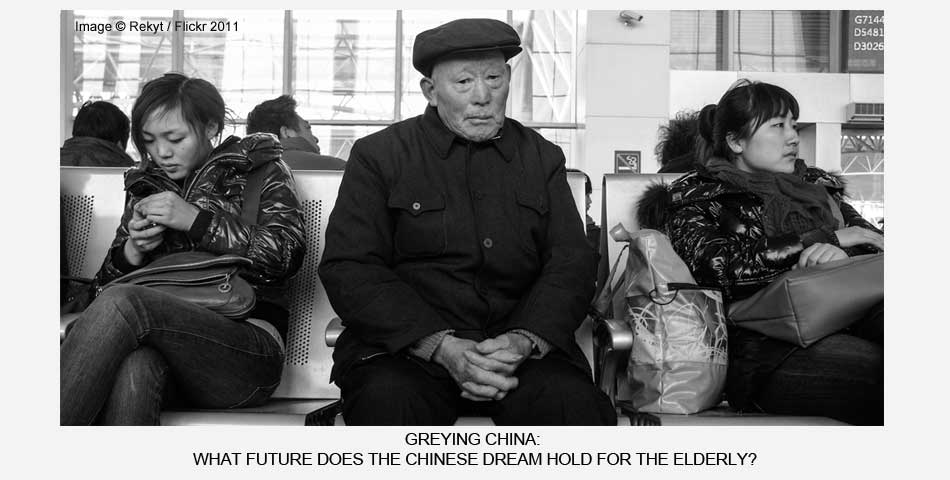

Twenty years after experiencing the benefits of this demographic shift, the situation is again changing. The former providers are retiring, and the much smaller next generation of single children is facing the daunting task of supporting China’s aging population. This situation is aggravated by the early retirement age in China, with women generally leaving the labour market at age 55 and men at age 60.

The implications of this demographic change are staggering, both for the economy and for Chinese society: today, roughly 123 million Chinese citizens are over the age of 65 – more than the entire combined population of the United Kingdom and France. In thirty years, every fourth person in China will be older than 65. In fifty years, it will be every third person.

China is quickly becoming a “4-2-1” society, in which one child has to shoulder the burden of caring for two parents and four grandparents. This development is already proving to be a major challenge to a country where traditional values like filial piety are no longer sufficient to keep young employees financing their elderly relatives, and where the pension and healthcare systems have not caught up to meet the evolving demands.

This week, we will discuss what the broad social, political, and economic implications of China’s demographic changes are, and what policy options might help alleviate the problems. Can the PRC’s social security be reformed on time, or are more and more Chinese doomed to be poor when they retire?

References

Wei, Zheng & Hao, Rui (2010): “Demographic Structure and Economic Growth: Evidence from China”, Journal of Comparative Economics 38, 472-491.

Share This Post, Choose Your Platform!

17 Comments

Comments are closed.

Short term relaxation of the one child policy can reduce the dependency rate. Combining this with long term reforms of the social security system and raising retirement ages would in my opinion solve China’s demographic problems. I would like to know from you guys what the negative consequences would be of these actions.

There are indeed a couple of negative consequences that could result from these policy changes. One of them is that a rise in the country’s birth rate could lead to a decline in the savings rate as more children per family have to be financed. This may weigh on investment growth, since higher savings rate means more money is available for investment. This is a problem for China as its growth is still heavily reliant on investments in industry, a very capital intensive sector.

After months of rumours Xinhua announced today that China will indeed relax its One-Child-Policy.

“The policy will be slightly relaxed so that couples will be allowed to have two children if one of the parents was an only child, Xinhua reported. Currently, both parents must be sole children to be eligible for a second child.” (http://edition.cnn.com/2013/11/15/world/asia/china-one-child-policy/index.html?hpt=hp_t3)

I would argue that the above mentioned shift is already sufficient in a sense that among most Chinese couples wanting to have children today at least one is an only child him/herself. Apart from that, the main complained against the OCP has been the associated forced abortions and the resulting gender imbalance. Theses problems should be largely irradiated through the published reforms.

From a pure economic point of view, I believe that most urban families will not want to have a second child nowadays, since paying for education is extremely high (e.g. university fees, private tutoring).

The effects of relaxing the OCP, might thus be small and the Chinese government might want to turn towards different measures to combat the demographic change towards an ageing population.

The article by Lin (2008) also states that as long as there will be more young people in comparison to old people, the social securities system can be sustained. Loosening the one-child policy could be a solution, however, this could have serious social and economic consequences. China already has the worlds largest population, with many overpopulated areas. If this will increases, this could lead to degradation of land and resources, pollution, and detrimental living conditions.

I don’t agree with Johannes that people will stick to having merely one child. Children are always very costly, that does not refrain most human beings from having more than one.

*if this increases (sorry for spelling mistakes)

China’s population is aging. To combat the aging population, China have to keep its population in balance. Every couple in China thus needs to have two children. One representing the father and one representing the mother. Then the population in China will remain about the same size. China is already on the right track with relaxing its One Child Policy, so that every couple is allowed to have a second child, if one of the parents is a single child. Considering that some couples may not want children or don’t want a second child, China could relax its policy a bit more and allow couples to have one till three children.

Many of the discussion participants seem to agree that allowing parents of which one is an only child to have two children is a good thing. I have two problems with this: 1) whether you are an only child is not your own choice, and therefore it is ethically irresponsible and unfair to allow such “only childs” to have more children than other couples, 2) the measure is not drastic enough to solve the increasing dependency ratio problem.

I’ll expand on argument 2. Wang Feng, director of the Brookings-Tsinghua Center for Public Policy, estimates that the measure will only add about 1-2 million births to the current 15 million births annually. I see no reason why this would be sufficient to resolve a situation in which every third person in China will be over 65 years in about 50 years. Johannes, you argued that “most Chinese couples wanting to have children today at least one is an only child him/herself” — where did you base this on?

Instead we should explore additional options. The basic problem is that the elderly dependency ratio is increasing. One improvement would be to increase the working-age population by increasing the retirement age (as suggested by Olaf), which seems fair considering the population’s increasing life expectancy. Another improvement would be to make the elderly more independent. For example, those elderly fortunate enough to dependent on their children only for physical help rather than financial help could instead go to so-called “homes for the elderly”, which are very common in Europe. Stimulating this privatized elderly care industry would also promote employment. The elderly that cannot afford such treatment will have to be taken care of through an improved pension system. This pension system should only apply to the less fortunate and not the wealthy elderly. While this is a drastic measure, it is drastic measures that are needed in drastic times.

Sources:

1: http://www.washingtonpost.com/world/six-questions-on-chinas-one-child-policy-answered/2013/11/15/ad64af1c-4def-11e3-be6b-d3d28122e6d4_story.html

To quickly respond to Tom’s question. I base this on the fact that the one OCP was introduced in the late 1970s. Thus people now in their mid-thirties, already a rather late age for having children in China, were born while the OCP was in effect. Therefore it can be assumed that at least one partner in a couple is an only child. Please correct me if my logic is wrong.

China`s demographic issue is getting a serious problem, no matter what side you analyze it from. The quote from Naughton describes it strongly when he writes that ” China will grow old before it has had the opportunity to become rich ”. The demographic transition in China is different from those in the West as most Western countries were already middle-to-high income countries when they experiences a demographic transtition. It seems now that China policymakers finally realize that something needs to happed. The question for us to answer is : Is it all too late ?

Couldn’t it be the case the there are still around 700 million farmers in the paddy fields that can be absorbed (urbanized and educated) and that there is enough working population for the next decades.

@Tom I thought I should share this video with you: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f4Yx_B25CJk&feature=youtu.be recently posted by CCTVInternational’s twitter account, which suggests a rise of the retirement age is in the offing.

On a similar note, there has been some positive noise made at the Plenum regarding a number of the potential solutions discussed here. For example this Reuter’s piece (http://uk.reuters.com/article/2013/10/17/uk-china-pensions-idUKBRE99G1BF20131017) gives a nice account of what might be going on behind closed doors with regards to pension reform.

Unlike some of the other reforms to come out of the Plenum, however, the demographic issue is one where I don’t feel confident that the simple withdrawal of the state intervention in family planning and pension scheme management (i.e. allowing forces of market and individual choice to direct reforms) would be overly prudent.

This is mostly because of the uniqueness of the demographic situation that current policy has created. It is superbly difficult to say what the Chinese people would do if a number of the controlling policies that we are discussing (hukou, one-child, allowing privatisation of pension schemes etc) were relaxed. The closeness of these issues to every (Chinese) person’s heart might mean that overly fast retraction of these policies would cause extreme reactionary developments: families having more children than they can support, people throwing all their money into badly run pension schemes, all of the countryside up and leaving for the city etc.

To go on out on a limb, I’m going to suggest that the key issue for me is that the state maintains a slow and tactical retreat from their old policies, so as to ensure that the reforms mentioned here have the outcome they are meant to have. My worst fear for these issues is that they become over-heated politically, which would inevitably lead to a clampdown and reversal that would not be in anyone’s favour.

@ Laura I don’t think this will solve all the implications caused by demographic shift. Moving more farmers to the cities is an unsustainable solution, as it will bring new difficulties in the rural areas and urban areas. Firstly, the rural areas will not have enough workforces to provide agricultural products, which are still needed. Additionally, it will cause a demographic imbalance, as it will only leave children and elderly behind. Secondly, the cities will have to create facilities to provide this huge influx of new citizens, which will, based on the current living conditions of migrant workers, not be well-organized.

Moreover, this option will not bring the needed solution to the ageing population, it is only a temporary solution to postpone the moment when the demographic problem reaches its peak.

I also suggest raising the retirement ages as one of the optional solutions. The age group of 25-54 years in 2013 counts for 46.5% of the entire Chinese population. If the government decides to raise the retirement ages, this age group can provide a sustainable working population for the next decades.

source: http://www.indexmundi.com/china/demographics_profile.html

I would like to stress that this problem not only involves economic concerns but also social concerns.

From an economic perspective, Nauman accurately points out that it is vital to consider this problem since China’s demographic transition emerges in a different stage than in Europe. However, in my view this development does not necessarily affect (future) economic growth as strongly as in certain European countries (e.g. The Netherlands). In China the negative effect will be partly offset since its population heavily invests into savings. The high savings rate will enable forthcoming pensioners to privately save and consequently partially compensate for the lack of state funded pensions.

From a social perspective, we should look at the effects of all these years of family planning on society. Generally, families prefer to have a son since they are expected to take care of the family. Hence, families often opt for an abortion once they find that their baby is a daughter. Nowadays, China has a population where the ratio of men to women is 100:120. This causes all kinds of various social problems. Newborn sons are often treated as ‘little emperors’ and cannot cope with the pressures of family and society. Moreover, men are not able to find wives, which causes further tensions. Ultimately, these pressures could lead to the emergence of ‘angry youths’, which are men who have an extreme neo-nationalist ideology.

When we put both aspects together it becomes apparent that we are dealing with a very complex issue. Therefore, I have shifted the discussion from a one-dimensional viewpoint to a more integrative, multi-perspective discussion. Most importantly, I do not believe that China has a grey future.

First of all, increasing the retirement age would be a good step to decrease the number of dependent people. As Shepherd pointed out any reform should be done in slow and tactical steps to prevent extreme reactionary developments. For this reason, China could perhaps look at recent examples in Europe where this measure is already taken (e.g. Netherlands, France). Second, women participation in the labor market should be encouraged. Females currently retire at an earlier age than men and are often full-time responsible for the household. The Chinese government should try to create incentives to increase participation of this part of the population. Third, relaxing the one-child policy is a step in the right direction from both an economic and social perspective. Families would have fewer incentives to abort their daughter since they can have a second try to born a son. Also, it may partially mitigate the increase of aging population on the long term.

Finally, I would like to critically debate some of the arguments stated earlier. Further capital accumulation or labor accumulation (pointed out by Laura) would just be a short-term fix of this problem. Also, encouraging ‘homes for the eldery’ (as Tom pointed out) could be an interesting avenue of exploration, however I do not consider it to be really viable in the Chinese context. This ‘European’ measure does not fit in with China’s collectivistic culture at all. Many families would never accept or entrust strangers to take care of their relatives. Lastly, Yonghui argues that in order to combat the aging population, every couple needs to have two children. However, I strongly wonder on what ground this claim has been made? I highly doubt that achieving this number is the fix to the current issue.

Following Hannie’s comment on moving farmers to the cities:

This might also cause over population in the big cities and might decrease the standard of living. This makes me think of the capital cities in South America. Lima (Peru), for instance, has 8 million people, 1/3 of the whole Peruvian population. The number of slums has increased substantially and thus higher inequalities in the city.

Going back to the core issue of the text, I believe that raising the retirement age will be a positive solution. Nevertheless, we need to ask ourselves, to what extend are people willing to work? We do not want to create a society that lacks the incentives and passion for work either.

The demographic change definitely is a big issue. But the planet is already at a point where more people would not be sustainable anymore, therefore China should keep the birth rate low. China in particular with is desastrous environmental condition should be especially interested in keeping it low. That means aging of the population would be inevitable.

The government therefore has to find ways how to help the old people sustain a purpose in life and not to be a burden for the state.

The purpose in life could be provided by easy jobs, as for example offering information in public places and also offering entertainment possibilities (free entrance to parks, sport facilities). For not being a burden for the state I consider the possibility to raise the retirement age.

As the introduction of this discussion suggests is aging a major problem in China. The demographic dividend is gradually turning into a demographic burden. The current pension system is so-called a ‘pay-as-you-go’ system, where today’s payroll taxes pay for today’s pensioners (The Economist, 2012). The Chinese government is working on the right construction of an institutional system that gives the elderly security. In addition, the Chinese tradition indicates a huge burden for the ‘children’. The Chinese tradition means that a child should take care of his/her parents and grandparents. The Chinese government has introduced a law that called “Protection of the Rights and Interest of Elderly People” (The New York Times, 2013). This law should ensure that children visit their parents more frequently and give them emotional support. I think that this law makes no sense, because no penalties are given as children neglect their parents and this law is not effective enough to tackle the aging problem. As Naumam said, is it not too late for China? I think that the Chinese government should come up with a clear retirement plan, where today’s pensioners not only be paid through today’s payroll taxes. The Chinese government should get the money for the pensioners somewhere else, for example by cutting back in other areas. I also think that the current retirement age of 55 year for women and 60 year for men needs to be increase, in order to reduce group of elderly people and increase the working-age population. Therefore, the Chinese government gets more time to implement a solution as the problem is spread over several years.

The one-child policy is one of the biggest causes of the aging problem in China. The Chinese government wants to be more flexible in this policy to address the aging problem. Many discussion participants consider this as a good solution. I think this is a good solution, but this solution will solve the problem only in the future and not the current problem. It will take years before the ‘new children’ can be attributed to the working-age population and may contribute to the financing of the today’s pensioners. It is also debatable whether parents want more children, since a small family is favorable within the Chinese community. Small families mean fewer children, but more money to invest in for instance the education of the children. Especially economic factors will be considered in the decision if parents want more children.

In short, I think the problem can now only be solved if the Chinese government eases the burden of the working-age population by adapting the current pension system, by getting more money through cutting back in other areas, and by increasing the retirement age. In addition, the one-child policy should be eases to address the aging problem in the future.

References:

The Economist. (2012) Fulfilling promises, http://www.economist.com/node/21560274, 18 November 2013.

The New York Times. (2013) A Chinese virtue is now the law, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/07/03/world/asia/filial-piety-once-a-virtue-in-china-is-now-the-law.html, 18 November 2013.

[…] ranging from issues in the financial markets and in international trade to questions about demographic developments, innovation, and environmental protection in the PRC. This week, in our final debate of the year, […]