Setting up a Discourse Analysis

Tips and tricks on how to create a professional discourse analysis project

You research politics and are interested in political communication? Then chances are your most common source material is the text, and rightly so. Much of politics is expressed through texts, and closely examining both written and spoken language can provide useful insights into the political position of actors or the rhetoric that informs an argument.

Yet exploring politics through texts is by no means easy. Conducting a professional analysis requires not only access to the right texts, but also time and possibly other resources. This can lead even experienced academics to cut corners. One understandable temptation might be to limit oneself to reading political texts, to summarize them for others, and to then offer a personal interpretation. This may be a legitimate way to produce a review of the relevant sources, but is it an actual analysis? I believe that an analysis has to be more systematic than this. More importantly, I think that good, confident research should be based on evidence and should be transparent, so that others can check the evidence.

In a previous post, I gave an introduction to the theory of discourse. In this post, I turn to the practical question of how to set up a discourse analysis. I will first discuss what is a good research question for a discourse analysis, and will then go over some of the fundamental issues you might want to settle before starting your project. Along the way, I will introduce you to a couple of analytical concepts and approaches that I find helpful.

Finding the right research question

Like with any type of research, a good discourse analysis starts with the right question. Before you pick your sources, and decide what tools to use on them, ask yourself: what is my concern? What motivates you to conduct this particular research, and what do you hope to achieve? For instance, are you trying to find out what the position of a particular government is on a specific topic? Do you want to explore how specific political actors made sense of a crisis event? Maybe you want to know what arguments informed a major political decision, or you want to see how a politician manipulated a debate. All of these are legitimate concerns that could stand at the beginning of a detailed discourse analysis.

Try to turn your concern into a question and then narrow the scope of that question enough to make it “operational”. This will allow you to find sources that promise to address your concern. A poor research question would be how South Koreans think about North Korea. This question is too broad, not to mention that it assumes we can find out what a large group of people actually think. A good research question, on the other hand, would be what position the South Korean President Park Geun-hye voiced towards North Korea during the 2013 crisis between the two states. This question has everything a good research project needs: relevance, a clear topic, potential sources, and a clear time-frame.

[frame_left] [/frame_left]In some cases, you may have simply come across a text that you liked, and that you feel deserves to be analysed. This is perfectly acceptable, but make sure you ask yourself what about the text attracted your attention. You likely had an implicit concern, and it is this concern that you can now turn into an explicit research question. Did a speech have a strong emotional effect on you? Then why not explore how the text elicited that emotion. Did the broad public reaction to a political debate intrigue you? Then how about trying to trace which arguments from the original debate made their way into journalistic texts and social media outlets, and in what form.

[/frame_left]In some cases, you may have simply come across a text that you liked, and that you feel deserves to be analysed. This is perfectly acceptable, but make sure you ask yourself what about the text attracted your attention. You likely had an implicit concern, and it is this concern that you can now turn into an explicit research question. Did a speech have a strong emotional effect on you? Then why not explore how the text elicited that emotion. Did the broad public reaction to a political debate intrigue you? Then how about trying to trace which arguments from the original debate made their way into journalistic texts and social media outlets, and in what form.

Without such a concrete agenda, you may still enjoy analysing the text that sparked your interest, but your hard work may not be able to carry a larger project, like a graduate or even post-graduate thesis. Pick your materials based on your questions, not the other way around.

Five points you should address before getting started

To narrow down your project and decide what sources and tools will be appropriate in your case, you may want to clarify the following five points:

1) What topic will you explore?

For instance, you could look at statements on national security, or statements on nuclear energy, or statements on health. The discourse analyst Siegfried Jäger (2004: 160-168) calls such general themes discourse strands. The idea is that such strands are intertwined, and that it can be helpful to explore not only what statements people make within one strand (Jäger calls such statements discourse fragments), but also to explore how one strand relates to others. Think of the disaster that struck Japan in 2011: what statements did various political actors in Japan make on nuclear energy before and after the event? How did these statements draw from assumptions, beliefs, and arguments that have their roots in the discourse strand on national security, on health, or on any number of other such themes? In short: define what topic you will analyse, and note down which various discourse strands you think might be important in that regards. These notes can then become your first coding categories: the analytical attributes you assign to different units of text, such as paragraphs, sentences, or even words, to later explore their distribution across the text, and their relation to one another.

2) What is your time frame?

There are generally two types of discourse analysis: the first focuses on a specific moment in time, and is called a synchronous analysis (Jäger 2004: 171). Discourse stretches out through time. Think of discourse for a moment as a bundle of intertwined wires, each with a different colour, that cross and twist as they stretch forward. These individual wires are the discourse strands, and the wire bundle is the discourse in its entirety. What a synchronous analysis does is dissect the bundle of wires at one spot and look at the incision: where is a specific wire located at that point? Does it touch other wires? The section where you slice into the discourse can be a major event that generates discussion. Such a discursive event could be an earthquake, or a terror attack, or an election.

The second kind of analysis looks at different sections of the wire-bundle and compares them. This is called a diachronic analysis, and is the sort of approach that the famous discourse theorist Michel Foucault favoured: he looked, for instance, at how the institutional setting of the hospital and the role of medical practitioners changed over time, and how these changes were a reflection of (and in turn an influence on) the kinds of “truths” that people held about health at different points in time (Foucault 2005/1989: 55-60).

3) What part of society is your analysis looking at?

[frame_right] [/frame_right]

[/frame_right]

Are you mainly interested in the discussions of politicians? Do you want to know how a political discourse plays out among academics, or in the press, or in private setting of people’s homes? Each of these different spheres, or discourse layers (Jäger 2004: 163), is interesting in its own right, but they also influence each other. Tracing how ideas travel between these layers through communication can be a rewarding analysis.

Think about the way in which an argument has influenced debates in different parts of society, for instance Samuel Huntington’s famous claim that the conflicts of the future will come from a clash of civilizations (Huntington 1996). How did this claim make its way into journalistic texts? When did politicians start positioning themselves and their political statements in relation to Huntington’s theories? What kind of statements did this lead to? These are the kinds of questions that a multi-layer discourse analysis would ask.

4) What medium and what language will you be working with?

A major decision on your part will be where you will look for discursive statements. You will need to be clear about the kinds of sources that promise to help you answer your question. A good analysis should explain what texts you used, where they came from, and why you chose them. You might decide, for instance, that your question is best answered by analysing Chinese newspapers, or speeches by Japanese politicians, or interviews with Korean activists.

If the source only exists in a verbal format, this does not need to stop you. You can transcribe such sources and turn them into written data, and can even add special markers to show intonations and emphases. Chilton (2004: 206) has provided a very useful list of such annotations.

Another important issue is whether your source material is already available digitally, or if you can somehow digitize your texts. It is possible to do a discourse analysis with paper-based sources, but digital texts allow you far more analytical options. Think only about how hard it is to do a text analysis without a search function. My advice would be to get your hands on digital versions of your sources, or to generate these yourself by typing up speeches, transcribing interviews, or scanning news articles and running them through software that supports Optical Character Recognition (OCR).

5) Will you need to work qualitatively or quantitatively, or maybe both?

If you are looking at one source, for instance a speech, a journalistic article, or a constitution, then your main concern will be with the kinds of discursive statements that this text makes, and the manner in which it makes them. In other words, you will likely be exploring qualitative aspects of the discourse. On the other hand, if your subject matter generates a large amount of text, for instance thousands or tens of thousands of words, then you will have a hard time deciding which statements to analyse in detail. In such a case, it makes sense to look at the numbers first, for instance by exploring which key words appear most commonly across the different texts.

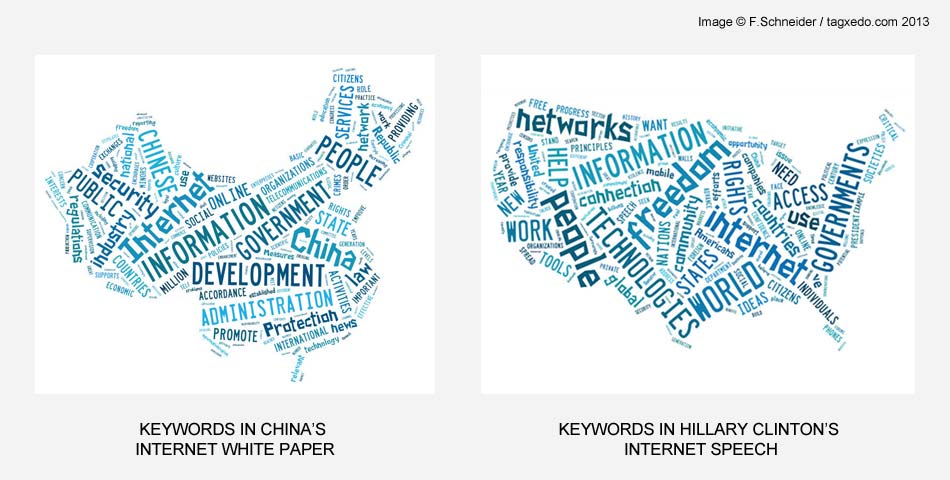

Word distribution can be an interesting research project in its own right, particularly if you can highlight major emphases in a text. Just take a look at the two very different word clouds below that I created as part of my own research on Digital Nationalism in China, using a handy visualization tool called Tagxedo. One cloud represents the most common words in the Chinese government’s white paper on the relevance of the internet. The other is a similar representation of key words in a speech by Hillary Clinton on the same topic. You can immediately see how different the two political positions are, and where the differences lie.

I personally use such quantitative analyses as a starting point: they can reveal regularities or irregularities across vast amounts of data, and can highlight which specific parts of the text corpus might then lend themselves to a detailed qualitative analysis. In the example, it might now be interesting to check which key words appear in close proximity with one another. It might also be worth analysing what exactly the Chinese government has to say on internet security, or how the word government is used in the text, or how the two different texts use the word people.

[frame] [/frame]

[/frame]

Gearing up for the next steps

Once you have made informed decisions on these five points, you are ready to formulate your question, pick your sources, and start your analysis. As you are get ready to launch into your materials, you may find the following step-by-step guide useful on how to conduct a discourse analysis, as well as the following advice on how to work with Chinese, Japanese, and Korean textual sources.

References

Chilton, Paul (2004). Analyzing Political Discourse – Theory and Practice. London: Arnold.

Foucault, Michel (2005/1989). Archaeology of Knowledge. 4th ed., London: Routledge.

Huntington, Samuel P. (1996). The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Jäger, Siegfried (2004). Kritische Diskursanalyse. Eine Einführung. (Discourse Analysis. An Introduction). 4th ed., Münster: UNRAST-Verlag.

Share This Post, Choose Your Platform!

34 Comments

Comments are closed.

[…] up a visual communication analysis is not that different from setting up a discourse analysis. The most important thing is asking the right questions, and then critically and systematically […]

[…] for instance my blog post on how to do a discourse analysis (which is about methods) or how to set up such an analysis (which includes epistemological […]

The posts on discourse analysis are simply brilliant! so clearly and neatly explained. Really helpful when you are snowed under with a pile of DA books. They have helped me and another classmate greatly.Thank you very much and congratulations for the blog.

Glad to hear that, Isabel. Thanks for the kind words.

[…] September 24, 2014 (Alochonaa): To conduct a discourse analysis, it is absolutely essential to work with original language materials. It is not possible to […]

HELLO!

I want to use the critical discoursanalysies as a metod for my school work and analys a american sit-com. Is this possible? It can be a problem to transcript the text to written text.

Best regards Lena

Dear Lena,

It’s definitely possible to use discourse analysis to analyse spoken words in TV, film, or radio shows, but you are right: you would need to transcribe a lot of what is being said. If that’s not what you are after (as in: if you are more interested in the visual discourse than in what is being said, linguistically), you could always try a visual communication analysis. I’ve got an introduction here on PoliticsEastAsia.com that might be helpful in that regard, in case you hadn’t seen it yet. Here’s the link: http://www.politicseastasia.com/studying/an-introduction-to-visual-communication-analysis/

All the best

Florian

is it possible to use critical discourse analysis as a theoretical framework for a research? please elaborate if it will do. thank you so much.

That depends on your project, but in principle: yes. But you would have to focus on the questions of epistemology (how we know what we know) that inform your approach to discourse. If you haven’t checked it out yet, see my post on discourse theory for a discussion: http://www.politicseastasia.com/studying/getting-the-hang-of-discourse-theory/.

Hi,

I’m writing my thesis on urban governance in Mumbai. My interest/question has to do with how the relationship between government officials and NGOs (plus slum communities) changed over time from adversarial to cooperative. I’m mainly focused on the communicative part of it. Do you think a discourse analysis is the right way to look at it?

Thanks in advance

Adriano

Hi Adriano,

I could imagine a discourse analysis for the kind of project you have in mind, but it’s not a prerequisite, I would say. It depends where your interests lie. If you are interviewing stakeholders or people affected by these collaborations, then you could indeed ask how they make sense of that sort of cooperation. How do they speak and write about it? What assumptions underlie their decisions? In a case like that, I would use interviews and any publications or documents that the various groups and players produce, and I would indeed give a discourse analysis a go. On the other hand, if you are not interested in these discursive mechanisms, then you could simply use similar materials to map out how the collaboration works and what its effects are. That would be more of a political economy or anthropology approach. You should of course still go through the materials systematically, and the kind of coding procedures popular in discourse analysis would also help there, but you wouldn’t need to examine language strategies. As always, I would advice putting together an approach that fits your question, and if that means mixing and matching various research methods and tools, then that should be entirely alright.

Hi Florian,

First of all thank you for creating such a easy to follow blog on discourse analysis! it was only yesterday that one of my lecturers introduced me to this particular methodology. I am currently looking at researching “what does good visual arts assessment look like in the middle years?” I am interested in looking at both curriculum documents and researched literature as a guide to investigate my question, I am just wondering if applying discourse analysis to this research is a good approach/process? I am just unsure of how to approach this methodologically at this stage (research proposal) – I have read soo much my mind is blurred.

Hi Katie,

I am tempted to give you a similar answer to the one I just gave Adriano (see above). It depends whether you plan to examine the kinds of strategic communication choices that your documents contain, or the assumptions and ideological frameworks that they draw from to make their case. If that is part of your question, then a discourse analysis makes good sense. If you are more interested in simply exploring what the content of your documents is, or if you hope the documents will give you access to other issues like school class dynamics and curriculum choices, then you can of course still use many of the analytic methods from discourse analysis, but I doubt you would need to explore the linguistic details of the texts. It’s a matter of where you want to take the project and what theoretical concerns you have. In any case, if you haven’t checked my other post yet on practical work steps in discourse analysis, take a look and see if any of these hands-on methods strike you as useful for your study (http://www.politicseastasia.com/studying/how-to-do-a-discourse-analysis/). Good luck with the project!

hi Florian!

i am going to do my thesis on critical discourse analysis of a politician’s speech! i just want to ask how should i turn his oral speech into written data? can you please help me?

thanks in advance!

Hi Uzma,

The answer to your question depends a bit on what you want the focus of your analysis to be. You’ll likely need to transcribe the speeches (so: write up what people are saying in order for you to have a digital, written version of the texts that you can then analyse), but whether you want to include all verbal elements of the speeches (e.g. phrases like “uhm”, “oh”) and mark all phonetic aspects (pauses in the speech, intonation, and so on) will hinge on the level of detail you plan to go into. You should be aware of such transcription practices, and you should then try to explain what choices you are making for your project and why. But you may not have to produce a complete transcription. For example, if you are trying to look at a specific theme across various speeches, then you’ll probably not be interested in the detailed verbal idiosyncrasies of the spoken word; you’ll be more interested in getting your hands on a lot of materials and then checking who says what in which context, and maybe also: who uses which words or phrases when talking about the topic. For a case like this, you could create protocols of your materials first, outlining only which topics are mentioned in what time interval. You can then collect all intervals that discuss the topic you want to analyse and then transliterate those parts. Exact intonation will probably not be of interest to you in such a case. On the other hand, if you are interested in the specific communication strategies of one or two political actors, then the detailed speech patterns might start to be interesting again. In such a case, you would use far less materials, but you would transcribe in a way that really captures all verbal elements of what is being said. That way you can later compare which parts of the speech had the speaker “trip up”, or which elements received specific oral emphasis, and so on.

Does this help with your question?

Thank you, man! Your tips and your Tagxedo idea saved my college seminar!! You rock!

Very glad to hear that. :)

Hi Florian,

I am finalising my proposal for a post-grad research project looking at framing of climate change from a rights-based perspective. I am basing the approach on a thesis that environmental issues can be effectively ‘bandwagon-ed’ onto existing human rights frameworks, providing ‘normative and rhetorical tools’ for addressing climate inaction. I am looking for links between existing framing typologies in climate change and rights-based discourse. Is it still considered a ‘discourse analysis’ if I am searching a range of documents for particular rhetorical strands, rather than doing a full analysis of the contents of those documents? Do you have any advice on how I should approach this methodologically, or suggest sources I can read on that type of analysis? This is my first time with discourse analysis. (I’m a distance student based in Vietnam, so can access online sources much more readily than books). I don’t like to presume on your generosity with time and advice, but it would be hugely appreciated – my supervisor is MIA due to illness. Thanks & regards, Cathrine.

Hi Cathrine,

Sorry to hear your supervisor is MIA. That is indeed tough. What you write so far sounds like you nevertheless have a good grip on your project. To briefly answer your questions: yes, a selective, qualitative analysis of several documents can still be a discourse analysis. What makes a discourse analysis about ‘discourse’ is ultimately your theoretical commitment to the idea that texts and social processes are connected (usually by the ways in which power and knowledge interact through language). Since you are clearly writing about an issue that connects politics and language, I think you should be able to make a good case for a discourse analysis, if you so choose.

As for how to deal with the materials, have you seen my advice here on this website? Here’s the link: How to Do a Discourse Analysis. You of course don’t have to follow all the work steps that are listed there, only the ones that you think help you answer your question.

I realize you’re not going to be able to follow up on a lot of the reading tips I’ve provided there, but you may want to see if you can get your hands on the following volume – it contains quite a bit of useful advice on how to analyze different types of materials (check out the amazon overview to see if this is at all helpful to you): Ruth Wodak’s edited book ‘Qualitative Discourse Analysis in the Social Sciences‘. Chapter 5 looks like it might be up your alley. Just a thought.

Good luck with the project!

Florian

Hi Florian,

Thank you very much for keeping such a helpful blog!

Currently, I am struggeling to find out what is the exact difference between a “(diachronic) discourse analysis” and a method called “conceptual history” (Begriffsgeschichte).

The latter method seems to be particularly big at Scandinavian universities (in the academic field “history of ideas”).

I have been looking into this “conceptual history” method for some days now, but I do not see how it differs from a diachronic discourse analysis. Do you perhaps have a suggestion?

Best regards,

Dan

Hi Dan,

This is a very good question. I can give you my take on what I think the difference is, but just a word of warning: I’m not an intellectual historian, so it’s entirely possible that professionals in the field of ‘Begriffsgeschichte’ will disagree with my understanding of their field. The way I see it, conceptual history is about tracing how different thinkers used and developed specific philosophical concepts. A question in that field might be how the relation between ‘reality’ and our ‘idea’ of reality (‘representation’) developed from Plato to Kant to Marx to Saussure to Wittgenstein. The task here would be to analyze what rationale the individual texts establish, and to contrast the nuances of meanings in the original sources, over time. This in itself can be quite similar to the kind of linguistic analysis that discourse scholars also conduct, but there is one major difference. Discourse analysis is also interested in how concepts and their relations were informed by, and in turn influenced, social practices and institutions at a particular time in history. So a discourse analyst, working with the same question, would ask: who exactly were Plato, Kant, Marx, Saussure, and Wittgenstein? What kind of societies did they live in, and how did the socio-historical context in which they worked influence how they developed their concepts? And: how did their theories translate into practices, for instance by shaping education policy, scientific agendas, political institutions, art and media, and so on? In other words: the social context and the question of how power works through the construction of knowledge are central to discourse analysis, whereas I suspect that most scholars of ‘Begriffsgeschichte’ would focus more strongly on text-immanent meanings and their evolution rather than on such socio-linguistic concerns.

Does this make sense? Let me know if you have a different understanding of the two approaches.

All the best

Florian

Could you, please, explain to me the best way to analyze media texts, and the steps that should be used in doing so? Thank you so much!

…just posted a reply to your other question. Hope it’s useful!

Hallo Florian, I am currently working on a research design for the cultural studies. I’m designing a critical discourse analysis of mental disabilities in one Hollywood movie. When it comes to analysing the data I’m not sure how to categorise the data. I’m orientating towards Fairclough’s model, who distinguished between ‘text’, ‘discursive practice’ and ‘social practice’. When I look at the movie I am not sure which data belongs in which category. It is clear that the transcript of the movie belongs to the ‘text’ section, also, I think, the movie itself with all the visuals. ‘Discourses Practice’ would be all production related data e.g. statement of producer, script, actor statement (is this still primary data) etc., whereas media reviews are ‘social practice’ as secondary data. Does this make sense ?

I would appreciate if you could give an advice.

Ciao

Schöne Grüße aus London

Hi Carolin,

Text, discursive practice, and social practice – a very good topic, and not at all trivial. I can tell you how I make sense of the differences, but at the risk of misrepresenting Fairclough. There might be nuances in his work I’m now overlooking. First off, I agree with you that the cultural product itself is the ‘text’ in this interpretation. I don’t particularly like using the term ‘text’, because it potentially obscures that something like a movie has elements that are specific to the medium, and that these elements may not work like regular written or spoken text. You already make this clear: ‘all the visuals’ indeed count as text, and so does the soundtrack, the dynamics, as well as any other element of visual communication that contributes to the discourse. We’re in agreement there, but I’m not sure I agree with the distinction between discursive and social practices you draw up. I would say that both of the levels that you describe are ‘discursive practices’, so the production process that leads to the cultural product as well as the reception of that product and any subsequent discussions it incites. As for social practice, I would include here the political implications of the discourse, so how the movie reflects and in turn (potentially) affects the interactions between people and the social institutions they are embedded in. So for example: if the movie depicts specific gender roles, then it is drawing from practices in the social realm as its ‘resource’ for discursive construction, and this construction may then affects such practices down the road. To give an example, something like gender-based discrimination on the job would be a social practice, the process of constructing a representation of that kind of discrimination would be a discursive practice, and the statements that in fact come out of that discursive practice would be the text. That, at least, would be my take on this distinction. Not an easy topic. Let me know what you think.

Best – F

Fantastically clear, comprehensive and really helpful. Thanks a lot for this.

Thank you Dan, that means a lot. Glad I could help.

Hi! I have a question about layers of discourse analysis. I am making presentation on this theme but didn’t understand in detail. Could you clarify them? Thank you for your answer in advance.

Hi there! A ‘layer’ is just the academic way of saying that discourses take place in different context or in different kind of places. For instance, news discourse would be one such layer: it is governed by particular scripts, specific power relations, habits and conventions, jargon, etc. In news, certain things are ‘acceptable’ discourse, and other things are not. Now compare that to the discourse in a pub. That discourse is also governed by specific conventions, but they differ from those that apply in news discourse. Each of these settings is a discourse ‘layer’. The ‘layer’ is a metaphor to say that the institutional setting matters, that the different settings are connected (for example when people in a pub discuss the news), and that all the different settings in a society together form the discourse in its entirety. I hope this helps!

Hi there, which tool are you using for building word distribution map? (as you did in the case of H. Clinton’s discourse)

Sorry for the late reply! I was in China, with limited internet access. That particular image is from Tagxedo. It’s a very nice little tool to visualize word distribution, and it works with Asian languages as well. If you are looking for something more analytical, I usually use NVivo, but that’s not a free programme. It does an excellent job at quantifying word-distributions, though, and it’s very powerful when it comes to qualitative analyses. Hope this helps!

Greatly useful as always.

Thanks! :)

[…] touch upon issues of identity and morality. The discourse analysis will thus be an analysis of discourse strands – ‘themes’ – in the text (Jäger 2004, as quoted in Schneider 2013). By conducting a […]