The Mass-Media Logic behind China’s Internet Controls

How the Chinese government is applying 20th century thinking to 21st century technology

One of the most popular technology myths to this day is that digital communication is difficult or even impossible to control – a sentiment that has been captured succinctly by John Gilmore’s argument that “the Net interprets censorship as damage and routes around it”. Critics of such arguments, like Evgeny Morozov (2011), have highlighted how various authoritarian governments in fact control information flows quite successfully, and the Chinese government with its Great Firewall has become a prime example of such digital communication management, and of Internet controls in particular.

A common way to discuss and assess how the Chinese authorities manage digital information is to frame the issue as a matter of domination vs. resistance: as a cat-and-mouse game between those who enforce censorship and those who evade it. This relation is often described in the foreign media as a struggle between an illegitimate authoritarian government and freedom-loving forces in Chinese civil society. While there is merit to the cat-and-mouse analogy when it comes to explaining how government critics creatively use language conventions and technical loopholes to get messages past the censors, this analogy is nevertheless misleading. It suggests that the Chinese leadership controls digital communication primarily to silence political dissenters, and that the logic behind China’s information management is to keep the Chinese Communist Party in control.

This logic plays a role in how propaganda and censorship work in China, but it does not tell the whole story. The Chinese government has opted for a specific approach towards digital communication, and to understand this approach we need to consider what ideological and economic rationales inform it, and how these rationales differ from the ones that are popular in Europe or America.

The Silicon Valley model vs. the Chaoyang model

The idea that digital technologies should be used to spread information freely and challenge authority has its roots in the American counter-cultures of the 1960s, and has found a prominent home in California’s Silicon Valley, among libertarian technology enthusiasts and neoliberal entrepreneurs ranging from Stewart Brand (Turner 2008) to Steve Jobs (Isaacson 2011). This Silicon Valley model is highly popular, not just among tech start-ups: its worldview has become engrained in European and American popular culture, as well as in the policies of liberal democracies. A good example is the Obama administration’s official Internet policy, captured in a speech by former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton in 2010. In this view, “the more freely information flows, the stronger societies become”. Digital technologies are creating “a new nervous system for our planet”, which can at times be “hijacked” and abused, but which should be put to use to defend “a single internet where all of humanity has equal access to knowledge and ideas”.

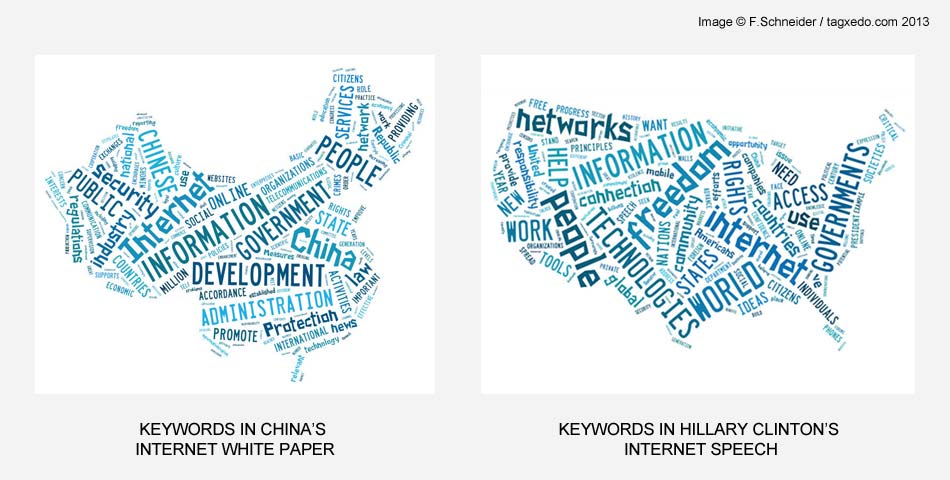

Chinese Internet politics follow a very different ideology, which has grown out of historical experiences with foreign encroachment on China’s territory during the so-called “century of humiliation”, with anti-authoritarian movements such as the May Fourth Movement or the Cultural Revolution, and with poor economic management before the start of the reform era. The result is an unapologetic authoritarian view that places a high premium on national sovereignty, social stability, and economic growth. It is precisely according to this logic that the Chinese government manages digital information in China today. This is apparent in the regulations that come out of the State Council Information Office, and its newly established Internet News Coordination Bureau, which work out of Beijing’s Chaoyang District. This “Chaoyang model” has little in common with the Silicon Valley model, as becomes clear when we compare Clinton’s speech with a similarly programmatic text on the Chinese side: the Information Office’s 2010 White Paper on the Internet in China.

A quick keyword comparison (produced with Tagxedo) shows that the White Paper has a very different focus than the Clinton speech: it promotes national security and national economic development, and it envisions the state as the actor that should ensure these outcomes. Where the Obama administration emphasises freedom, the Hu Jintao administration emphasises security. Where the US vision sees global networks, the PRC vision sees national development. According to the White Paper, the purpose of the Internet is to spread “China’s splendid national culture”, “publicize government information”, and help “the government get to know the people’s wishes”. In other words, the 2010 roadmap for China’s Internet management is an extension of the CCP’s existing mass-media policies, which holds fast to the belief that information flows should serve national interests and should be carefully vetted by professionals to prevent unauthorized “rumours” from endangering social stability.

The net as a mass-dissemination device

The Chaoyang model takes the logic of mass media, and consequently the 20th century logic of information dissemination, and applies it to the digital technologies of the 21st century. This leads to diverse outcomes in different areas of digital communication, but the underlying rationale nevertheless remains the same: that only authorized information, produced by and disseminated through a small number of media outlets, should reach the public. Information flows, in this view, require professional gatekeepers.

On China’s web, this means that the major sources of information are large websites run by officially accredited organizations. In my own research, I am currently mapping networks of websites that deal with nationalist issues, and it turns out that the key nodes in these networks are government institutions and large state-owned media conglomerates. The two most important players are the State Council and the Ministry of Information Industries. What is more, different websites rarely link to other websites and generally reproduce information that has been handed down from state sources such as China’s news agency Xinhua. The Chinese web, at least on the issues I have examined, functions largely as a mass-dissemination device for official information, much like a television station that broadcasts on different channels.

The situation is somewhat different in the blogosphere, as well as in the realm of microblogging, where users post and re-post comments on diverse topics. Yet here, too, the state aims to recreate its mass-media system: digital services are available through a small number of Chinese companies, such as Sina or Tencent, and these providers have to follow (and enforce) national legislation on what “healthy” online behaviour should entail. For the Chinese state, this approach is doubly beneficial: it promotes economic growth by strengthening national champions of industry while at the same time allowing open discussion to take place in walled gardens that can be more easily monitored and censored. What is more, the combination of this centralized system with various government practices that punish vaguely defined bad online behaviour facilitates self-censorship on the part of users – much like such practices facilitate self-censorship among professional journalists.

Conclusion: the costs of the Chaoyang model

Contrary to the arguments by cyber-optimists like Clay Shirky, who believes that digital technologies will make the Chinese Communist Party obsolete by 2020, the authoritarian Chaoyang model is in fact very successful in assuring that the CCP remains in control of China’s information flows. The issue with this model is not whether or not it works, but what it costs. Much has been made of the large sum of money that the Chinese government spends on domestic security measures, which includes policing the Internet. Yet this sizeable investment is not the main cost. More importantly, by applying a mass-media rationale to digital communication, the Chinese authorities are buying social stability at the price of potential innovation and creativity. As Yochai Benkler (2006: 272) has argued, the major economic benefit of digital connectivity is that individuals are no longer “consumers and passive spectators”, but can become “creators and primary subjects” who collaborate openly in highly effective and innovative ways.

These benefits, however, are reduced when users only access digital networks to retrieve vetted information, but do not share controversial ideas or opinions because they have to fear the potential repercussions that such information exchanges might entail. In other words, by restricting the “noise” that accompanies networked communication, the authorities are also restricting what is known as the emergent properties of networks, which are precisely the properties that produce unforeseeable innovations. This should be a major concern to China’s State Council, which co-produced a recent report with the World Bank on China’s economic future: the report lists innovation and creativity as crucial ingredients for turning the PRC into a high-income country. Yet as much as the Chinese leadership recognizes the need to create a “knowledge economy”, its policies remain torn between the conflicting goals of social control and open knowledge exchange. As long as the priority remains with the former, as is likely going to be the case at this week’s Central Committee plenum, the PRC will continue to pay a high price for its Chaoyang model.

This post has also appeared on Nottingham University’s China Policy Institute blog.

References

Benkler, Yochai (2006): The Wealth of Networks – How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedom. New Haven & London: Yale University Press.

Isaacson, Walter (2011): Steve Jobs. New York et al.: Simon & Schuster.

Morozov, Evgeny (2011): The Net Delusion: The Dark Side of Internet Freedom. New York et al.: Penguin Press.

Turner, Fred (2008): From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press.