What North Korea Has to Do with the 2013 German Election

And do Germans who refuse to vote support Kim Jong-un?

Yesterday, on 22 September 2013, the German citizens voted. The conservative Christian Democrats won in a landslide, prompting a commentator in the Spiegel to re-christen the German Federal Republic “Angela-Merkel-Land“. Since I hail from the German city of Hamburg, I have been mulling over whether I should devote a blog post to this election. I had originally decided not to comment, since the 2013 German election do not really fit the scope of “Politics East Asia”. But then I came across a political comic that changed my mind. It is a comic that deploys the images of political figures from Asia to argue that it is bad, indeed immoral, not to vote.

In this post, I therefore want to first take a look at that argument before then discussing the comic and various similar attempts to make political statements by referencing politics in Asia. I will also explain why I think that non-voting is not at all an immoral political action, and will conclude by sharing with you my own voting choice in the 2013 German elections.

The German discourse on non-voting

When I went to school in the 1990s, the politics and ethics classes I took promoted a very specific political norm: that voting in national elections was not only good civic behaviour, but was morally imperative. A common phrase in that context was “those who do not vote, vote right-wing”. It is important to recall the context of this discourse: Germany was undergoing a difficult process of reunification, and German neo-fascist youth groups were increasingly in the news for attacking foreigners. A particular concern at the time was the perceived popularity of right-wing politics in East Germany, which was struggling to overcome economic stagnation and the political disillusionment that this stagnation had brought about.

The worries that right-wing parties might again exploit social conflicts to cease control over German politics was very real in my mind at the time, and has remained so following the success of various right-wing parties in Europe, for instance in Austria, the Netherlands, Denmark, or most recently Greece. Considering that the nationalist party “Alternative for Germany” only narrowly missed the parliamentary cut-off rate in yesterday’s German election, it seems to make sense to argue that any vote not given to a mainstream party, and preferably a left-leaning party like the Social Democrats or the Green Party, is a vote ceded to the radical political right.

What is wrong with this picture?

The week before the 2013 German elections, a Baden newspaper published a political comic that reiterated this attitude towards non-voting. The image has since circulated through social media, and is available on the paper’s website. The image carries the title “non-voter” (in German: “Wahlverweigerer”, which literally means “election-refuser”). It shows a droopy-eyed man with a sleeping cap slouching about, thinking out loud “voting is really useless”.

In the background, various vicious-looking characters are agreeing emphatically with that sentiment: “we say yes to this”, they proclaim. A closer look identifies these figure as a pantheon of autocrats. Aside from Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe, we have an array of Middle-Eastern figures such as Syria’s President Bashar al-Assad, Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Kha, and Saudi Arabia’s King Abdullah bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, but also an unidentified hooded figure who presumably stands for Al Qaida or the Taliban. From the “Far East”, these men are joined by the Burmese Senior General Than Shwe, by the North-Korean supreme leader Kim Jong-un, and by a Chinese cadre who I have some trouble identifying. The glasses and facial features are probably meant to signify former president Jiang Zemin, though it is possible that the cartoonist had Hu Jintao in mind, or even the new Prime Minister Li Keqiang.

In the background, various vicious-looking characters are agreeing emphatically with that sentiment: “we say yes to this”, they proclaim. A closer look identifies these figure as a pantheon of autocrats. Aside from Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe, we have an array of Middle-Eastern figures such as Syria’s President Bashar al-Assad, Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Kha, and Saudi Arabia’s King Abdullah bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, but also an unidentified hooded figure who presumably stands for Al Qaida or the Taliban. From the “Far East”, these men are joined by the Burmese Senior General Than Shwe, by the North-Korean supreme leader Kim Jong-un, and by a Chinese cadre who I have some trouble identifying. The glasses and facial features are probably meant to signify former president Jiang Zemin, though it is possible that the cartoonist had Hu Jintao in mind, or even the new Prime Minister Li Keqiang.

It would be a moot point to stress that China is not North Korea, or that lumping together political and religious leaders, as well as diverse systems ranging from warlordism to military junta to one-party state, is a gross oversimplification of political realities. Political satire is arguably not a genre that preoccupies itself with subtleties. The message here is then also fairly straight-forward: those who refuse to participate in political elections are lazy, negligent sleepyheads, whose ignorant actions benefit authoritarian governments. “If you do not vote”, the comic seems to mock, “your society may soon look like Syria or North Korea!”

The threat of authoritarian politics

This use of authoritarian clichés has been en vogue for some time in European and American political discourse. A particularly popular target in this respect is China, though other societies in Asia receive their fair share of mention as well. A recent example of a political campaign that milked fears of China to support its agenda is the American political commercial that Citizens Against Government Waste released in 2010, titled “The Chinese Professor”. The video has since received over 2.6 million hits on Youtube, and has been re-released in 2012 as part of the NGO’s website DefeatingtheDebt.com.

In the video, a conservative message about deficit spending is driven home by conjuring up a dystopian world in which America is “owned” by a techno-Maoist version of China, replete with Cultural Revolution iconography. A Chinese professor in a near-future lecture hall narrates the fall of empires in history, concluding with the US. Due to its deficit spending, so the claim, American hegemony in the world came to an end, and Americans now consequently “work for us”, the Chinese. This conclusion elicits gleeful and somewhat sinister laughter on the part of the Chinese lecture audience. The implication: only if Americans cut social welfare can such a nightmare scenario be avoided.

As lamentable as such “Yellow Peril” rhetoric is in a privately funded advertisement, the following publicly funded video by the EU commission is arguably even more deplorable. In it, a Caucasian woman, dressed like Uma Thurman in Tarantino’s film Kill Bill (ironically itself an homage to Bruce Lee), fends off various “attackers”: a Chinese Kung Fu master, a saber-wielding Sikh warrior, and a Brazilian Capoeira fighter. The solution to the “threat” that these card-board stereotypes from the BRIC economies pose, is that the EU needs to be enlarged. In the video, the European woman spawns a series of clones who surround the three attackers in a circle of peaceful meditation, prompting them to sit down and join in. If we are to believe the EU commission, then European enlargement not only fends off the threat that other cultures and their economies allegedly pose, but manages to turn the foreign barbarians into civilized people just like “us”. Understandably, this video garnered so much criticism that the commission decided to retract the campaign.

Orientalism as the argument that ends all arguments

These examples have two things in common. Firstly, they exploit the perception that the values of liberal democracies are under attack by those who promote authoritarianism. Particularly the importance of China in world politics today heralds for many a shift in power towards the “East”, and with it towards what Cooper Ramo has called a “Beijing Consensus” about how to conduct politics. That alleged consensus is then believed to promote a rigid authoritarianism in the service of a neo-liberal capitalist development programme, which does not place a particularly high premium on the kinds of civil liberties that the EU stands for. The fact that eloquent speakers like Eric X. Li are defending neo-authoritarian modes of governance in renowned forums like Foreign Affairs or TED only fuels such concerns.

Li’s arguments deserve to be critically discussed in more depth, and I hope to do so later this year. Personally, I think Li is misinformed, not only about politics in China, but also about how politics generally work in the information age. Be that as it may, neo-authoritarian arguments are not really the point when political campaigns in Europe or the US try to scare citizens to action by conjuring up images of an exotic, unpredictable and dangerous “other”. This then is the second commonality in these campaigns: they are examples of what Edward Said (1978/2003) has called “Orientalism”.

Such Orientalism may be blatantly racist, and worryingly ignorant of Europe’s colonial past in Asia, but it is effective: it takes a political issue, such as not voting in an election, and then shuts down any discussion about the topic by shifting the focus to a fake sense of urgency. This urgency, often constructed as a “Clash of Civilizations” (Huntington 1996), then serves as an argument to end all arguments (I will not discuss Huntington’s thesis here, but can recommend Edward Said’s insightful critique).

Why non-voting is not an endorsement of authoritarian politics

In the case of the German political comic, such Orientalism-to-end-all-arguments is deployed to delegitimize a political opponent: the non-voter. Non-voting, in this discourse, does not deserve a discussion. It is dangerous, and thus needs to be thoroughly discredited as “bullshit”, to borrow a phrase from one of Germany’s most sophisticated and respected newspapers, Die Zeit.

What makes non-voters so dangerous is that they are not necessarily lazy sleepyheads, and that they may not prefer authoritarianism to democracy at all. Not casting a vote is a political statement. That statement might be that the non-voter is dissatisfied with leading political actors. The recent discussions about politicians’ secondary incomes and the influence that industrial lobbies have on German politics has not done the legitimacy of these actors any favours. Neither has the manner in which the government and parliamentary opposition have reacted to recent economic and political crises. The abysmal situation that German-backed austerity measures have had in southern European countries are just as much credible causes for dismay as the inability of German political leaders to shed light on the government’s involvement in the prism surveillance scandal.

However, as serious as such concerns are, they still raise the question of how an act of inaction is supposed to be a useful political response. After all, the German political system features 29 parties to choose from, each with its own distinct policy agenda. Some of these parties are radically opposed to the politics of the current ruling party, or even the politics of all four mainstream political parties. Surely any vote that is not cast is also a vote that is not cast for one of these opposition actors. In other words: non-voting seems to facilitate the status quo.

At least three arguments can be made against such a view. Firstly, while non-voting indeed does nothing to change the status quo in parliament, it nevertheless challenges this status quo. It is, after all, a radical gesture on the part of citizens to retract their political approval from precisely this status quo. A vote for an opposition party implies that the voter is willing to accept the rule of the election winner, even if that winner is not the party he or she voted for. After all, the opposition may win a future election, and in that case the oppositional voter would expect all citizens to equally abide by that outcome. A vote is a conformation of this rationale, whereas a non-vote is its rejection.

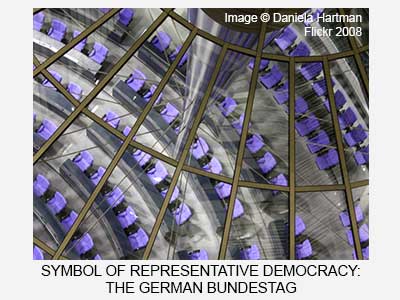

Secondly, the act of non-voting may be a way to start a more fundamental discussion about the current parliamentary system’s ability to assure “democracy”. Every generation has to renegotiate what democracy means. The established view in Germany, for instance, is that politics is a complex affair that requires expert knowledge. In order to balance the need for efficient governing with a fair way to include as many social groups as possible in the process of policy-making, the founders of German democracy opted for a representative setup. In such a system (Strom 2000), the people elect parliamentarians every four years from a pool of different political parties, and the most popular of these parties then sends a representative to head the German government. This head of government then selects a number of ministers to run the different arms of the bureaucracy, and this cabinet of leaders needs to have the approval of parliament. The ministers are put in charge of complex bureaucracies, staffed with expert specialists on topics as diverse as finance, social welfare, education, foreign policy, etc. Over the course of the subsequent four years, the bureaucracy is supposed to enforce the policies that parliament agrees on, and the original voters keep an eye on these processes through an independent mass-media.

Secondly, the act of non-voting may be a way to start a more fundamental discussion about the current parliamentary system’s ability to assure “democracy”. Every generation has to renegotiate what democracy means. The established view in Germany, for instance, is that politics is a complex affair that requires expert knowledge. In order to balance the need for efficient governing with a fair way to include as many social groups as possible in the process of policy-making, the founders of German democracy opted for a representative setup. In such a system (Strom 2000), the people elect parliamentarians every four years from a pool of different political parties, and the most popular of these parties then sends a representative to head the German government. This head of government then selects a number of ministers to run the different arms of the bureaucracy, and this cabinet of leaders needs to have the approval of parliament. The ministers are put in charge of complex bureaucracies, staffed with expert specialists on topics as diverse as finance, social welfare, education, foreign policy, etc. Over the course of the subsequent four years, the bureaucracy is supposed to enforce the policies that parliament agrees on, and the original voters keep an eye on these processes through an independent mass-media.

This setup has its advantages, but it arguably places a higher premium on efficiency than on participation. This is understandable considering that it has traditionally been impossible to involve a community of tens of millions in complex, often urgent processes of political decision-making. However, there are various reasons why the logic of this system may be in need of revision. For instance, the idea that a professional bureaucracy is an effective way of governing is worth rethinking. More often than not, bureaucratic politics are anything but “efficient”. The faith in “expert knowledge” should similarly be treated with caution. Philip Tetlock (2006) has written an excellent book on this subject. And finally, the idea that mass-media are a more effective “fourth estate” than alternative forms of political communication has been strongly questioned by scholars like Yochai Benkler (2006). Considering that new communication technologies are increasingly making it possible for large communities to collaborate on complex, dynamic civic issues (Shirky 2013), the time may indeed have come to renegotiate how democracy should work.

Finally, even where non-voters simply signal their dissatisfaction without spelling out an alternative, they should be taken seriously. Criticism does not have to be constructive, as philosopher Raymond Geuss (2010) recently argued. During a colloquium in The Hague, Geuss recounted the story of a man who had broken his leg, and had to wait most of the day at the hospital before being treated. The patient complained to the chief-of-medicine, who tersely responded that he was aware of the problem, but did not have a solution – unless the disgruntled patient could come up with a better way of managing the hospital, he had better be quiet.

I do not know how Geuss feels about non-voters, but the point he was trying to make with his example was that complaining is a legitimate act of critique. It is not the patient’s job to come up with a solution for how to run the hospital. It is, however, the chief-of-medicine’s job, and he should take the complaint seriously and work towards developing a better system. I am inclined to agree with this attitude. Then again, I grew up in a city where the highest form of praise is: “I can’t complain”.

How I would have voted

During yesterday’s elections, I did not get to vote. The election slip was stuck somewhere in Hamburg, while I was in China on research leave. This is not all that different from the last two elections (one local, one national), which I also missed because the documentation did not reach me in time. Such delays are understandable, I suppose, considering that I was quite far away, in the Netherlands.

If you are wondering who I would have voted for in these latest elections, I would have changed my voting behavior for the first time since I was 18. In past elections, my vote had always gone to the social democratic party. For the 2013 German election, the “vote-o-mat” of the news magazine Spiegel assured me that my political allegiances had shifted, and that my views were now in line either with the Left Party, or the Feminist Party, or the Green Party, or the Pirate Party. Since the vote-o-mat is not designed to assess my concerns about representative democracy in the 21st century, it shall be forgiven for not being entirely accurate. This year, I would not have voted for any of the political parties, I would have voted not to vote. It is a shame I did not get the chance. I was actually looking quite forward to it.

References

Benkler, Yochai (2006): The Wealth of Networks. How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedom. New Haven et al.: Yale University Press.

Geuss, Raymond (2010): Politics and the Imagination. Princeton and London: Princeton University Press.

Huntington, Samuel P. (1996): The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. New York: Touchstone.

Said, Edward W. (1978/2003): Orientalism. London et al.: Penguin Books.

Shirky, Clay (2013): Cognitive Surplus. Creativity and Generosity in a Connected Age. London et al: Penguin Books.

Strom, Kaare (2000): “Delegation and Accountability in Parliamentary Democracies”, European Journal of Political Research, 37: 261–289

Tetlock, Philip E. (2006): Expert Political Judgment: How Good Is It? How Can We Know? Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Share This Post, Choose Your Platform!

2 Comments

Comments are closed.

Thanks for an interesting blog. I disagree, though, with what you read into the cartoon: rather than implying that we will become another Syria, North Korea or whatever authoritarian/dictatorial country, I think the cartoon reminds us of the fact that the right to vote is far from being realized in every country, while many of us are simply too lazy or too disinterested to cast a vote. I agree that non-voting can be a political statement but doubt that this is the case with the majority of non-voters. And, as always, I would prefer ‘doing’ to ‘complaining’: everybody is free to found or join an existing movement in order to change things for the better. Also something you can’t do in the states that the cartoon is featuring…

Thanks Barbara for these thoughtful comments, and apologies for the late reply – China has been keeping me busy.

I agree with you that joining a movement or actively being political in our day-to-day lives is important. I am not convinced that this is the argument of those who criticize non-voters, though. I have the impression that such criticism focuses more on the idea of the lazy or disinterested citizen. But in such cases the burden of evidence lies with the critics: is it really true that non-voters are simply lazy and/or ignorant? And even if it is true, why is that so?

Overall, I would much rather place the emphasis on the kind of activities you mention, even (or especially) when they are “small-scale”. I think arguments that frame voting as the supreme democratic behaviour are overall misleading, since they downplay other forms of political activity. Politics happens in many ways, and electoral processes are only one domain, and IMO not the most important one.