Political Communication at the Shanghai Expo

Why theories of domination and resistance do not tell the whole story of how mass-media events work

Every few years, a selected country has the honour of hosting one of the prestigious World Exhibitions: a fair that calls together the nations of the world, its major international organizations, and many of its leading businesses, to showcase diverse views on a specific theme. The most recent of these events was the 2010 Shanghai Expo, which received particular attention since many journalists, politicians, and scholars believed it to be a rite of passage for the host country: it offered the People’s Republic of China the opportunity to continue the public relations effort it had started two years earlier, at the Beijing Olympics, and through which the authorities were hoping to demonstrate that China was a modern, prosperous, and harmonious society. The Expo now gave the organizers in Shanghai the chance to similarly lay out “the vision of the world from the Chinese people’s hearts”, as one Chinese art director put it.

I visited the Expo for several weeks in the summer of 2010 to explore how such an event works, and what political relevance it might have. The open-access academic journal Asiascape Ops has recently published my research on the official theme pavilions, and I’d like to take this opportunity to accompany that article with a blog post. I’ll try to sum up a few of the concerns that the Asiascape Ops paper deals with, but more importantly: I want to share some of the controversies, anecdotes, and impressions with you that I think make studying mass-media events like world fairs a fascinating and important topic of research.

I will start with some of the arguments that have traditionally been made about world fairs, and which still inform the discussions about such events and their politics today. These arguments are mainly about the way in which an event like the Shanghai Expo tells a seductive story about capitalism and nation-states, and how such discourse might end up dominating the perspective of the visitors. As attractive as such arguments are, I am not convinced that they tell the whole story. So I’ll follow up on this discussion by showing you what I think such accounts of world fairs are missing: that visitors of mass-events do not necessarily behave the way that critics tend to assume, and that the events themselves do not necessarily tell one unified, domineering story about capitalism and nation-states to begin with.

Domination and world fairs

If I had to pick one word to sum up the Shanghai Expo, I would probably have to settle for “overwhelming”. In case you visited the Expo, drop me a line to let me know what your first impression was. My guess would be that you probably felt similarly awed as I did, and if that is the case, you and I are in good company: many journalistic accounts of this massive event have commented on the scale, for instance the Guardian and the Atlantic, and the people I talked to at the Expo seemed to have similarly shared the sense that this brilliant barrage of spectacular lights, sounds, and images was breath-taking. I myself was reminded of visiting Disneyland for the first time as a kid, and indeed the Shanghai Expo very much presented itself as a theme park – only that this theme park was about ten times larger than Disneyland.

Considering how disorienting and overwhelming a mega event like this can be, it is small wonder that many commentators feel troubled by such spectacle. This uneasiness has a tradition: world fairs have received much criticism for showcasing reductionist accounts of foreign cultures, and the history of these events is indeed awash with examples of blatant racism, sexism, and other offensive themes. The fairs of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, for instance, celebrated colonialist world views, leading historians of these events to interpret them as tools of imperialism (e.g. Rydell 1985). Take the example of the Paris World Fair of 1889 with its highly orientalist street scenes of medieval Cairo. Timothy Mitchell (1989) has argued that this exhibit not only reflected but also reinforced European misconceptions about Egypt and the so-called “Orient” – misconceptions that at the time rightly baffled and offended Egyptian visitors to this miniature Cairo, but that nevertheless prevailed, even among those Europeans who had actually visited Cairo.

Contemporary world fairs may have left much of this unapologetic colonial history behind, but their combination of reductionist world views and spectacular presentations continues to elicit critique. William Callahan from Manchester University has recently written about the Shanghai Expo (Callahan 2012), voicing concerns that the event spelled out a shiny but simplistic story of capitalist modernity and “harmonious” world order. His former student Astrid Nordin has gone one step further by arguing that this particular spectacle was so overwhelming that it effectively seduced visitors into loosing themselves in its fakeness and abandoning their ability to critically judge the world outside the Expo – an interpretation that follows the arguments of French philosopher Jean Baudrillard (1983).

I sympathize with many of these arguments, probably because anything involving large masses of people coming together, especially for state-endorsed events, reminds me of the staged events that the National Socialists in Germany used to shore up support for their ideology. Mass propaganda, mob dynamics, and uncritical collective actions make me cringe. I don’t feel comfortable going to a national football match, or an official parade, and some of you may find this discomfort exaggerated. However, I think that those of you who went through similar schooling as I did might just share this view, and along with it sympathy for critics that continue the tradition of critical anti-totalitarians like Hannah Arendt, Walter Benjamin, Max Horkheimer, or Theodor Adorno. After all, the German Nazi regime made frighteningly effective use of mass media and mass events to sell its propaganda, so it seems only prudent to ask whether mass culture in an age of ubiquitous multi-media exposure might be similarly problematic, or even dangerous. This includes scepticism towards the seemingly seductive world fairs.

But how valid are worries about world fairs like the Shanghai Expo really? At the risk of oversimplifying what is of course a very complex and intricate debate, I think the concern can be narrowed down to two arguments: that world fairs present a unified discourse that promotes certain interests, and that such fairs have the power to dupe visitors into adopting this ideology as their own. I think that both of these arguments are to some extent mistaken.

Why mass-events do not dominate visitors

Let’s start with the argument that Expos have the power to trick people into adopting certain views. Here is a collection of letters and news phrases from the 1889 Paris World Fair, narrated onto images of that event. What is striking here is how these enthusiastic comments take for granted that the stereotypes on display represented foreign places as they “really” were. English-language news media have reported similar comments from the Shanghai Expo, for instance of a Chinese visitor arguing that his visit to the Tajikistan pavilion was “really like a visit to Tajikistan”, or a Chinese couple commenting that the Expo allowed people “who never would have a chance to go abroad” to “experience the whole world”.

I don’t want to dismiss that ideas spread through culture, that media play a crucial role in this regard, and that such mass-communicated ideas might, under certain circumstances, influence people’s perceptions. But does mass culture really shape people’s views as strongly as critics claim, and are terms like domination or hegemony really the best way to conceptualize how mass communication works? I hope to at some point conduct an actual reception analysis with visitors of mass events to explore this issue in detail, but my suspicion is that mass communication has far less power than is often assumed. I find the arguments of those who study active audiences and participatory media convincing that people do all sorts of things with cultural products, often in ways that producers would not have anticipated. Henry Jenkins (2003) has provided insightful analyses of fan culture and of cultural “remixing” that demonstrate this.

As for world fairs, I had an interesting interview with one of the organizers of the Australian pavilion that I think nicely sums up the case. I asked what effect all the elaborate exhibits at this event might have on visitors, and in particular what he thought of the many pavilions at the Expo that tried to educate visitors in one form or another – whether through official CCP propaganda, or through demonstrations of ostensibly European or American values. I received the refreshingly honest answer that pavilions harbouring ambitions of teaching audiences valuable life-lessons were forgetting that most visitors did not actually care about such lessons. Someone might be dragging their little kid along in 40°C, while pushing an aging parent around in a wheelchair, occupied with thoughts of getting out of the lengthy queue outside a pavilion and into the cool, air-conditioned exhibit inside. Then that visitor gets pushed along through the pavilion, coming out the other side with thousands of other visitors, already looking for the next attraction that will finally make the kids stop whining.

Such observations had long convinced my interview partner that he could be content if visitors to the Australian pavilion realized that they had just been to the Australian exhibit, not the Austrian exhibit. As he put it, placing the emphasis on didactic content would be pointless: “if there isn’t a beech or a furry animal in the room, you’re doing it wrong”.

This is of course only one anecdote, but I am inclined to agree with this pavilion organizer. In fact, recent research into world fairs has shown that visitors do not readily adopt the stories that pavilion organizers try to sell them. James Gilbert (2009) has looked at the 1904 St. Louis World Fair, which is now infamous for both its didactic ambitions of teaching American visitors about foreign cultures and its problematic depiction of “uncivilized” peoples. Analyzing personal reports from that time, Gilbert finds that despite the prevalence of colonialist themes, visitors of the event “often missed cues meant to guide them to certain conclusions because of private musings, idiosyncratic desires, and unconstrained imaginations. They frequently did not see what was intended to be seen, or they misread it, sometimes willfully” (ibid.: 4). It seems that if there really was a dominant, imperialist story presented at that fair, the visitors at least did not automatically buy into it.

Did the Shanghai Expo tell a dominant story?

The effects of mass events, and of media in general, remain an exciting field full of controversy, but regardless of how you feel about the power of a world fair to influence people, there is still the question of whether world fairs really have one dominant ideology that they try to impress on visitors.

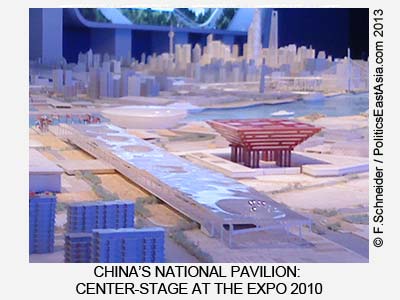

The Shanghai Expo surely presented several prominent themes. A whole range of pavilions showcased technological improvements, made by multi-national corporations, and the idea that capitalism was the best mode of producing such improvements was (at least implicitly) present in many of the commercially funded exhibits. Then there is the fact that the event put a strong emphasis on nation-states, with each “nation” presenting a reductionist story of what that respective country was supposedly all about. The idea that it was important to be from a specific country with a specific culture was consequently at the forefront of the event – an idea that is by no means self-evident, as anyone familiar with rivalries between cities like Liverpool and Manchester, Hamburg and Munich, or Shanghai and Beijing will be able to testify. And then there were the various Chinese pavilions, most notably the national pavilion at the centre of the Expo territory, which had been designed by PR experts to present ideas in line with official CCP propaganda.

The Shanghai Expo surely presented several prominent themes. A whole range of pavilions showcased technological improvements, made by multi-national corporations, and the idea that capitalism was the best mode of producing such improvements was (at least implicitly) present in many of the commercially funded exhibits. Then there is the fact that the event put a strong emphasis on nation-states, with each “nation” presenting a reductionist story of what that respective country was supposedly all about. The idea that it was important to be from a specific country with a specific culture was consequently at the forefront of the event – an idea that is by no means self-evident, as anyone familiar with rivalries between cities like Liverpool and Manchester, Hamburg and Munich, or Shanghai and Beijing will be able to testify. And then there were the various Chinese pavilions, most notably the national pavilion at the centre of the Expo territory, which had been designed by PR experts to present ideas in line with official CCP propaganda.

Yet despite several such common themes, the exhibits were highly diverse, often standing in stark contrast with each other or even being contradictory in themselves. This is what my research article on the theme pavilion explores, but there are many other examples. The stories of nationalism, for instance, did not neatly carry over into the different city pavilions, and neither did the stories of capitalism. Similarly, the official Chinese promotion of a harmonious society was somewhat awkwardly juxtaposed with a range of different interpretations of what “harmony” might mean. While China’s national pavilion and many other Chinese exhibits relayed the official interpretation of harmony as social order and economic stability, other actors played with and reinvented the concept to suit their own purposes. The Japan pavilion, for example, set out to promote harmony between the Chinese and Japanese people – not an easy task in China, where memories of the Sino-Japanese War and the actions of revisionist, nationalist Japanese politicians frequently cause strong resentments. In this pavilion, harmony was not the outcome of inter-governmental relations between nation-states, but the outcome of small-scale cooperation between Chinese and Japanese environmentalists trying to save an endangered crane species.

Many foreign pavilions similarly tried to break down and reinvent what they perceived to be official message on harmony, but we don’t need to turn to foreign national pavilions to find such creative engagement with this seemingly overarching theme. Here is one of the videos by the Chinese animation artist Bu Hua that was on display at the Future Pavilion’s “Harmony Square”. The focus here lies on minimalist stories of a small group of children who try to live in harmony with nature – not exactly a story that collapses with the way in which Chinese officials conceptualize “harmony”.

Conclusion: why Expos matter

Whether you agree with me that mass events have little power to make visitors adopt a certain world view or not, I hope to have at least given you some indications that the Shanghai Expo did not present visitors with any such readily adoptable, unified view. It was a diverse event with a multitude of stories, ideas, and arguments. Many of these ideas were ideological, and several exhibits were demonstrably manipulative, but I think that seeing an event like this through the lens of “domination” vs. “resistance” is not the best way to capture its full complexity and figure out how mass events work.

This does not make studies of mass events like the Shanghai Expo any less important. The 2010 Expo had a massive transformative effect on the city of Shanghai, which revamped its infrastructure in ways that have noticeably changed the metropolis and affected millions of people. Such outcomes in themselves are important dimensions of mass events that are worth exploring.

Then there is the fact that many pavilions, particularly the official Chinese exhibits, had the explicit intention of teaching viewers valuable lessons. Even though I am not convinced that such didactics work, the exhibits still give us a valuable glimpse into the political agenda of those who made them. If the Chinese organizers are putting up displays to showcase their “vision of the world”, then maybe it is worth taking a look at what that vision is. I think this alone is reason enough to take such events seriously, and to try and study them for the political messages they relay.

References:

Baudrillard, Jean. 1983. Simulations. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e).

Callahan, William A. 2012. “Shanghai’s Alternative Futures: The World Expo, Citizen Intellectuals, and China’s New Civil Society.” China Information 26: 251-273.

Gilbert, James. 2009. Whose Fair? Experience, Memory, and the History of the Great St. Louis Exposition. Chicago & London: The University of Chicago Press.

Jenkins, Henry. 2006. Fans, Bloggers, and Gamers – Exploring Participatory Culture. New York & London: New York University Press.

Mitchell, Timothy. 1989. “The World as Exhibition.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 31, April: 217-236.

Nordin, Astrid H. M. 2012. “Taking Baudrillard to the Fair: Exhibiting China in the World at the Shanghai Expo.” Alternatives: Global, Local, Political 37: 106-120.

Roche, Maurice. 2000. Mega-Events & Modernity – Olympics and Expos in the Growth of Global Culture. London & New York: Routledge.

Rydell, Robert W. 1985. All the World’s a Fair – Visions of Empire at American International Expositions, 1876-1916. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.