Making Sense of the Recent Chinese Propaganda Campaigns

Does the visual rhetoric mean that Mao is back?

I have recently been terribly inconsistent in blogging, mainly because I have been busy with research in China. However, while I have been working on my project on Sino-Japanese history in Chinese online networks, I have also been collecting examples from the most recent propaganda campaign that the Chinese leadership launched as part of president Xi Jinping’s attempt to promote the “China Dream“. I am not yet sure what to make of these diverse materials, but hope that my colleague Hwang Yih-jye and I will have the chance to analyse them in more detail as we work on our project on cultural governance. What the visual aesthetics and slogans reminded me of, however, is the current discussion in the English-language media on how the Chinese leadership is allegedly harking back to the Maoist ideology of its past in an attempt to cement its rule. In this post, I want to discuss the role that so-called “red” iconography plays in contemporary Chinese propaganda, and why I am not convinced that the use of such iconography spells a Maoist revival for China.

The specter of Mao

In the wake of the leadership transition in China, many media outlets in Europe and the US have been following the emerging political agenda of China’s new president Xi Jinping, speculating what kind of leaders Xi and his colleagues in the Politburo Standing Committee will turn out to be. Most recently, reports have emphasised how the government has tried to reel in critics and dissidents, how it has started a rectification campaign against corruption, and how it has launched a new wave of propaganda in support of its ideological vision for China. The Wall Street Journal interprets this as evidence that China’s leaders have embraced Mao, while the Financial Times sees in these strategies a revival of “Mao’s propaganda tool kit”.

These developments seem particularly auspicious considering the recent purge of Bo Xilai, the high-flying Chongqing party chief who had successfully milked China’s revolutionary past for songs and images to increase his popularity, but then fell from grace in the wake of corruption charges and crime scandals. One of the realizations in much of the media reporting abroad has been how the very people who purged Bo are now deploying his seemingly Maoist rhetoric themselves. To many, such mass-line campaigns are eerily reminiscent of the Cultural Revolution, and various liberal intellectuals in China have voiced concerns that China could turn down this path again.

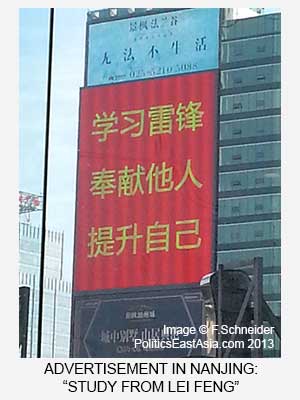

The observation that China’s new leadership is invoking its revolutionary past is itself accurate. Xi Jinping recently called on his compatriots to ensure that “the color of red China will never change“, and China’s official news agency Xinhua has outlined how Mao’s example is meant to serve the anti-corruption efforts. Meanwhile, the Communist martyr Lei Feng is again en vogue as a model for China’s “socialist core value system“. The photo on the left, which I took in August 2013 in Nanjing, attests to this: like other announcements flashing across digital advertisement screens in major Chinese cities, this one calls on its audience to “study from Lei Feng, dedicate oneself to others, and improve oneself”.

The observation that China’s new leadership is invoking its revolutionary past is itself accurate. Xi Jinping recently called on his compatriots to ensure that “the color of red China will never change“, and China’s official news agency Xinhua has outlined how Mao’s example is meant to serve the anti-corruption efforts. Meanwhile, the Communist martyr Lei Feng is again en vogue as a model for China’s “socialist core value system“. The photo on the left, which I took in August 2013 in Nanjing, attests to this: like other announcements flashing across digital advertisement screens in major Chinese cities, this one calls on its audience to “study from Lei Feng, dedicate oneself to others, and improve oneself”.

All of this leads to an important question: Is the Chinese leadership trying to bring back the Maoist past? Many of the foreign media resources I have linked to above seem to suggest that this might be the case, and the mass of 1950s to 1970s iconography deployed by the state and the Party today seems to prove this point.

Five reasons why Mao is not back

Despite these tropes from the repertoire of the CCP’s “red” rhetoric, I would be very hesitant to suggest that China’s new leadership and its propaganda are “Maoist”. This is not to say that I am not skeptical of the recent anti-corruption campaign, or that I want to belittle the increased attempts at media control that have accompanied it. In fact, I hope to discuss these media control issues in a separate blog post soon. However, I think that much of the foreign media reporting on China misrepresents the role that Mao and his revolutionary legacy play in contemporary Chinese politics, and that it obscures the way that PRC politics work in the wake of the recent leadership transition. Here are five reasons why I think that speaking of a Mao revival is misleading.

1) Not everything that is red is about Mao.

Communist ideology is still very important in Chinese politics today, but much of what becomes associated with Maoism in the English-language press actually describes a much more complex set of ideas, officially consisting of Marxism, Leninism, and “Mao Zedong Thought”. All three systems of thought are codified as guiding principles in the PRC’s constitution, suggesting a unified ideology, but that should not detract from the fact that they represent very different and often contradictory sets of ideas (for an introduction, I can recommend Joseph 2010).

At the risk of being vastly simplistic on this complex subject, Marxism is an analytic perspective that sees history as fundamentally guided by material struggles over the means of production. To Marxists, social progress comes about as societies get increasingly entangled in the social and cultural contradictions of their economic systems, and then overcome these contradictions either through revolution or evolution. Chinese Communist Party cadres today are Marxists at heart, and even their most capitalist policies are not necessarily at odds with their Marxist ideology: in the Marxist view, China needs to pass through a stage of capitalism before it can evolve into a fully socialist country, much like many European social market economies are believed to have done.

Leninism serves as an organizational principle. In the Leninist view, a society cannot overcome its “contradictions” unless it has a properly-trained Marxist vanguard that leads the people towards socialism. In other words, Leninism justifies one-Party-rule, and explains how that rule should work: through “democratic centralism”, i.e. a political deliberation process that consults various parts of society on issues of policy-making, aims to relay these views upwards through the Party, and then centralizes decision-making in a central body (usually the Politburo and its Standing Committee). The higher up the hierarchy, the more egalitarian and “democratic” the decision-making process is supposed to become, but once a decision is reached, it has to be enforced with unified conviction at all levels of the Party structure.

Maoism has had a love-hate relationship with both of its ideological cousins. Not only did Mao reject the Marxist and Leninist bias towards urban production, focusing instead on China’s vast agricultural hinterland. More importantly, Mao became convinced that the rigid Leninist Party system would itself become the breeding ground for bureaucracy, corruption, and ultimately capitalist revisionism. Maoism therefore promotes a popular grass-root anti-authoritarianism that attacks (often violently) any form of hierarchy and tradition – an approach that has had disastrous outcomes. However, since these outcomes are not broadly discussed or taught in China, it is not hard to see how this populist idea might be attractive to those who feel disenfranchised by the overbearing bureaucracy of the Party and state, and by the current leaders’ perceived capitalist agenda.

So while there are indeed supporters of (certain) Maoist ideas in China today, it would be a mistake to conclude that Chinese politics generally follow those ideas. Much of Chinese politics is demonstrably and unapologetically authoritarian, drawing much of its inspiration from Lenin and Marx, but overall this approach to governing China is in many ways at odds with what “Maoism” originally stood for.

2) The red themes are not “back”, because they were never gone.

Much of the recent reporting on propaganda and ideology in China focuses on how the “red” rhetoric connects to the PRC’s recent leadership transition, and I agree that the recent rhetoric should in part be understood as a response to the hindrances that this transition has faced. However, this focus on 2013 risks obscuring that the recourse to China’s revolutionary past is by no means unique to the present leadership. In fact, the previous administration, under the leadership of Hu Jintao, has drawn quite strongly from these traditions.

Consider the 2009 anniversary of the PRC, which the leadership celebrated with a lavish military and civilian parade. The event was heavily laden with red iconography, at the time prompting the Financial Times to compare the event to mass parades in North Korea, and to argue that China was reveling in “Mao, Marx and the Military”.

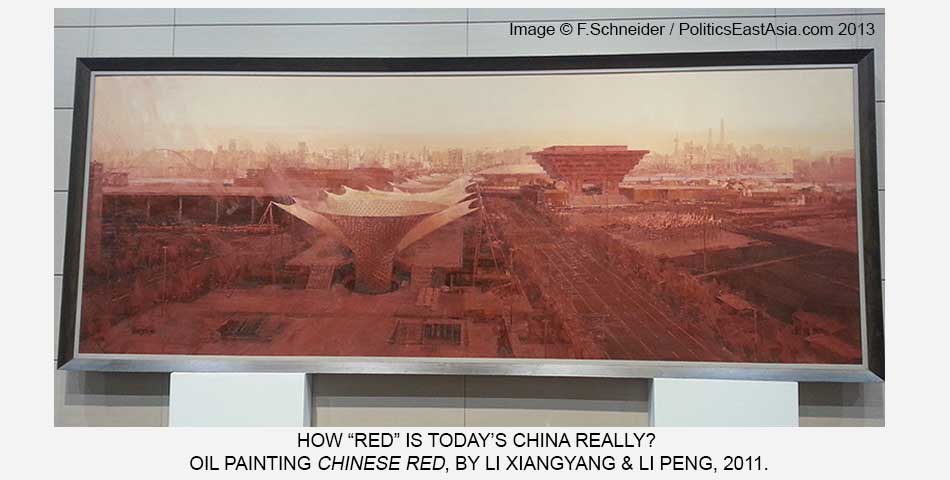

Another recent examples of red iconography is the 2010 Shanghai Expo, and particularly the official China Pavilion, which included not only nostalgic memorabilia from the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, but also movies that deployed model workers, peasants, and soldiers to celebrate the Chinese “masses” and their vanguard leadership. Much of the imagery was designed specifically to resemble the socialist realist iconography of Mao-era propaganda.

And then there is the 90th anniversary of the CCP in 2011, which was accompanied by a host of events and a barrage of propaganda. The image at the start of this post, which commemorates the Expo, is a testament to this – it is called “Chinese Red”, and at the time of writing was on display at the China Art Museum in Shanghai, as part of an exhibit called “China Dream”.

3) Red iconography and rhetoric are only a small part of the big picture.

The red tropes may seem ever-present, but what is important is that they are only one part of the CCP’s public relations strategy. The current “China Dream” campaign is a good example of how CCP propaganda creatively mixes various different traditions. This includes references to China’s pre-modern past, particularly the complex set of ideas and quotes often associated with “Confucianism”. Quotes from the Confucian Analects abound, as do strategically placed characters such as “virtue” (de 德) or “filial piety” (xiao 孝).

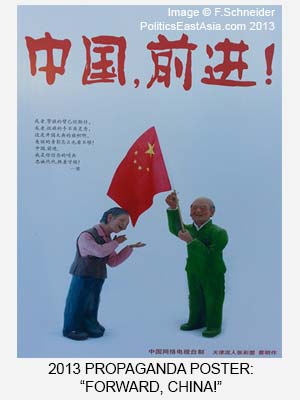

However, just as this very selective use of traditional political thought hardly heralds a “Confucian revival”, so too does the socialist realist artwork in other posters not spell a “Maoist revival”. In fact, the current “China Dream” campaign distinguishes itself through a creative eclecticism that seems to leave no cultural resource untapped.

However, just as this very selective use of traditional political thought hardly heralds a “Confucian revival”, so too does the socialist realist artwork in other posters not spell a “Maoist revival”. In fact, the current “China Dream” campaign distinguishes itself through a creative eclecticism that seems to leave no cultural resource untapped.

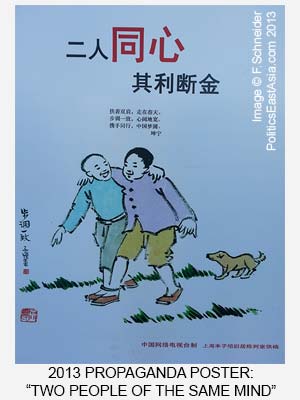

Consider the poster I have added on the right. It not only deploys visual artwork reminiscent of the 1930s, but augments the visuals with a quote from China’s arguably most obscure literary source, the Book of Changes or I Ching, to drive home its modern communitarian message: “If two people are of the same mind, their sharpness can cut through metal.”

4) Mao tropes are not about Maoism, but are a set of shared symbols.

The portrait of Mao is arguably among the most recognizable icons today. His image, as well as the iconography of the Mao era, have been used and reused in art and pop culture to such a degree that they have become “undemonized”, as Dal Lago has put it in her review of Mao-art. Mao, as an icon, does not necessarily point towards a specific ideology, but instead has become part of a shared set of symbols. This set of symbols encompasses not only the socialist realist tropes of the Mao era, but also pre-modern visual tropes, recognizable artwork of the 1920s and 1930s, imagery of urban development that characterized the reform era, and symbols of national renewal from the 21st century, such as Beijing’s Olympic architecture or the images of China’s first “spacewalk”.

Evoking these symbols is not about spelling out a policy agenda, but rather about appealing to a sense of belonging and shared destiny. It is this propagation of shared signs that constructs a sense of the nation, or what Benedict Anderson (2005) has called the “imagined community”. The CCP’s revolutionary past has a firm place in this effort at community-building, since it elicits fond feelings of nostalgia. Referencing the Mao era is about providing the “epistemological comforts of home” (Hardin 1997: 89), or in other words: eliciting a sense of belonging by appealing to people’s comfort zone.

5) Mao’s meaning is under construction.

Finally, as much as Maoist icons are today often deployed as “empty signifiers”, they at times do get used to make statements about China’s revolutionary past, and about how to interpret Mao’s legacy. What is interesting in this respect, however, is how the CCP is actively reinventing Mao in ways that are often radically different from the ideas Mao himself promoted.

The 2009 PRC anniversary is again a good example of this. Hwang Yih-jye and I have analyzed both the parade and various cultural products that were released around the time of the anniversary (Hwang & Schneider 2011), and we have found that Mao is ironically made to serve a neoliberal capitalist agenda. In the parade, the Mao era is de-emphasized to the point where the event celebrates almost exclusively the past 30 years in PRC history, not the past 60. Similarly, in an official propaganda film that narrates the “Founding of the Republic“, Mao and his ideology are brought into close proximity with that of his rival, the nationalist Chiang Kai-shek. In one scene, Mao even admits that entrepreneurship is necessary to keep the nation running – an interesting spin on a man who notoriously prosecuted entrepreneurs as “black” elements of society. Such examples show how the meaning of Mao is being re-calibrate by China’s propaganda workers to bring the revolutionary past in sync with the arguably capitalist present.

So why the Mao hype?

Even if you agree with me that the revival of Maoism in contemporary China is exaggerated, the question is still: why does the current leadership use so many Mao tropes?

To me, the answer lies in the way in which the CCP attempts to justify its rule over China to the PRC’s citizens. It is important to realize that successive administrations have been very concerned about their political legitimacy, particularly after the fall of the Soviet Union and the end of Communism in Europe. This concern has only been aggravated by the many social, economic, and environmental problems that China faces today.

To me, the answer lies in the way in which the CCP attempts to justify its rule over China to the PRC’s citizens. It is important to realize that successive administrations have been very concerned about their political legitimacy, particularly after the fall of the Soviet Union and the end of Communism in Europe. This concern has only been aggravated by the many social, economic, and environmental problems that China faces today.

The lesson the Party has learned, in part by studying its own past, in part by studying foreign scholarship and practices, is that any attempt at justifying CCP rule in China must be based on the broadest foundation possible. This means assuring general welfare through sensible economic policies. It also means reforming Chinese politics to make government transparent and fair to those who are affected by its decisions. Finally, it means creating a sense of national unity and appealing to different social groups with selected PR messages.

It is this last part of the CCP’s “legitimacy mix” (Schubert 2008) that is currently receiving the most attention. This is in part because the new leadership has indeed increased its attempts to legitimate its rule through propaganda, probably to assuage worries about potential social, political, and economic instability in the wake of profound changes: a large-scale political reshuffle, a looming economic crisis, and various threats to the country’s territorial integrity. It is in part because foreign journalism on China sells best when it tells China Threat stories, and few things are as threatening to Europeans and Americans as the thought of a economically powerful Maoist China.

However, despite the influx of red propaganda, I would urge caution before jumping to the conclusion that China is embarking on a new Cultural Revolution. Such arguments ignore that China’s revolutionary past is currently hotly and critically debated in China. They also potentially get in the way of understanding how Chinese economics and politics work in our present age. This is not to say that China’s current propaganda strategy should be endorsed or excused. My argument is that looking more closely at what motivates such propaganda and what its contents actually are may help us understand what is happening in Chinese politics today, in the wake of a highly complex and in many ways fragile power shift from one leadership generation to the next.

References

Anderson, Benedict (2006): Imagined Communities. London and New York: Verso.

Hardin, Russell (1995): One for All – The Logic of Group Conflict. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hwang, Yih-Jye & Schneider, F.A. (2011): “Performance, Meaning, and Ideology in the Making of Legitimacy: The Celebrations of the People’s Republic of China’s Sixty-Year Anniversary”, The China Review, 11 (1): 27-56.

Joseph, William A. (2010): “Ideology and Chinese Politics”, in Joseph, William A. (ed.): Politics in China: An Introduction. Oxford et al.: Oxford University Press: 129-164.

Schubert, Gunter (2008): “One-party rule and the question of legitimacy in contemporary China”, Journal of Contemporary China, 17(54): 191–204.

Share This Post, Choose Your Platform!

4 Comments

Comments are closed.

[…] a dystopian world in which America is “owned” by a techno-Maoist version of China, replete with Cultural Revolution iconography. A Chinese professor in a near-future lecture hall narrates the fall of empires in history, […]

Informative piece.

Regarding the existing contradiction between empty signifier and element of meaning, the same too broad an intellectual brush on part of chinese policy thinkers/intellectuals can be seen in this fascinating panel discussion with nial ferguson, joschka fisher and ronnie chan, filmed in Ukraine abou a month

ago. http://m.youtube.com/watch?v=GhGUxjtpRcU

In my opinion, ronnie chang’s position is a bit of a philosophical cliche, while also disregarding indian influence on his “holistic” explantion of “asia-ness”. Almost as if he is repeating the cliche’s that non-chinese think and say about china.

I’m curious about you opinion on the things said by the panel.

Thanks for posting this. I haven’t had a chance to watch it yet, but will try to do so asap.

[…] blog: http://www.politicseastasia.com/staging/3558/research/chinese-propaganda-campaigns/ […]