Debating Digital Convenience

A Discussion with Students at Leiden University

It’s easy to get cozy online. Today’s internet is divided into sophisticated apps, each providing us with increasingly convenient ways to communicate and go about our daily affairs, often seemingly for free. But considering that these offers are run by large corporations that profit from our data and free labour, we need to ask: are we enthralled by the convenience that corporate apps and services provide?

Digital convenience has in some cases become so essential to everyday life that it is hard to imagine our societies without them. In China, platforms like Sina’s microblogging app Weibo, Tencent-invested Bilibili livestreaming platform, or Alibaba’s range of digital and e-commerce services have inserted themselves into all manner of social processes. Tencent has been able to expand its chat app Weixin to the point that it now incorporates numerous lifestyle maintainability capabilities, like online booking and payment options that have few rivals outside Alibaba’s similarly powerful Alipay. Weixin is now so popular, it is doubling as a virtual ID system for Chinese citizens. Even without the Great Firewall of China that prevents competition with foreign services, China’s app market is so compartmentalized that one has the wonder whether users have voluntarily locked themselves away behind digital walled gardens.

However, we do not need to turn to China and its carefully state-controlled digital ecology to encounter the power of convenience. Across Asia, Facebook remains a dominant provider of news and information, despite wide-spread concerns over the company’s business and information-management practices. In Taiwan, Facebook’s penetration rate looks increasingly like a rounding error off of 100 percent. This, in turn, has raised questions about the malleability of public opinion and the threat of misinformation in Taiwan’s highly polarized public sphere. Similarly, the chat app LINE is extremely popular in Japan, Taiwan, and other Asian markets, and Line’s parent company Naver is working hard to corner the market for news information in South Korea. Meanwhile, Naver’s competitor Daum invites Korean users into tempting digital spaces of convenience through its highly successful digital platform Kakao.

As early as 2012, digital security expert Bruce Schneier referred to these processes around the world as ‘digital feudalism’. In a world where everyday interactions are increasingly monopolized by profit-seeking corporations with intransparent policies, oblique algorithms, and little to no public oversight, are we giving up important public and private processes for simple convenience? Is the ‘platformisation’ of digital spaces the new normal, for digital spaces, or is it merely a phase on the road to yet different configurations of digital media ecologies? And what lessons can we learn, in this regard, from highly advanced digital societies in East Asia? These are some of the questions our grad students at Leiden University’s Institute for Area Studies are debating this week. Join us in the comments section with your thoughts and ideas.

Share This Post, Choose Your Platform!

36 Comments

Comments are closed.

To follow up on this week’s readings, here is an article that shows the (possible) dangers of search engine’s advertisements and the influence of these ads on users. The search engine discussed in the article is Baidu. This article raises the question: should search engines first check which company is engaging in advertising on the results page? Who is responsible for this?

https://qz.com/674030/baidu-chinas-version-of-google-is-evil-a-growing-number-of-users-say/

Another interesting aspect of the business model of search engines is how highly competitive it is. As discussed in the article of Min Jiang, Baidu rarely refers to competitors such as Hudong Baike. Competition between Chinese search engines is fierce. It turns out that companies even adapt keyboards in order to prevent users getting redirected to a competing search engine (which was halted by the Chinese court):

https://www.scmp.com/tech/big-tech/article/3028920/court-orders-search-engine-stop-hijacking-rivals-traffic

Have search engines a special responsibility to offer users the most relevant content (even if this leads them to competitors)? Or is this just a form of normal competition between different, competing businesses?

Interesting article! I would say it’s a social responsibility for search engines to show the most relevant content regardless of their competitors. We have come to rely on search engines in our daily lives to such an extent that it is unthinkable to not use them. Therefore I think search engines and especially the market dominators have a responsibility to give as much accurate and relevant information possible. However we do then get into the issue of regulation. How can we make sure search engines adhere to that principle and is it even possible for us to regulate this as they are technically private companies? Especially when the diversion away from competitors is more subtle and goes more unnoticed than the incident the article describes.

How would you define ‘most relevant content’? For a search engine company like Baidu, Naver or Google, the definition of such terms (and the results this leads to) are inherently different from what scholars on the subject, consumers, politicians and governments might deem most relevant. I think this week’s readings show that there are several actors at play that determine these results. This makes it almost impossible to answer your question. Should the search results be more diverse (incl. competing companies): yes, I personally do agree with that. But I believe enforcing such things is nearly impossible.

Your questions also touche upon a broader subject, not necessarily related to just search engines but digital platforms in general, as to what extent such companies should fact check advertisements. In the U.S. this has been part of public debate quite a lot recently and it raises interesting questions on the responsibilities and tasks of digital platforms. In the ‘Trumpian’ era where things as facts don’t seem to matter anymore, these debates have also become highly politicized. I believe that yes, to an extent companies such as Google or Facebook, but also their Chinese, Korean or Japanese counterparts, should do basic fact checking of advertisements if they do not what to become pools of disinformation.

I agree with your comment Jelena, and I think it is also important to look at what the role of governments should be in fact-checking and preventing fake-news to enter social platforms. However, when the government gets involved, this will probably cause a lot of dissent among users since the government could in theory ‘protect’ itself by using censorship on online anti-government activities.

This question of to what extent governments or private companies should ”filter” content on social media and other online platforms also refers back to the article of Fuchs (Seminar 4) in which he showed great similarities between Chinese and US social media companies.

If search engines (companies) would be publishers, of course they should be held personally accountable for spreading their (dis)information, but if they are (public) platforms, who is to say they are responsible for censoring other people’s content? This question lies at the heart of the discussion in the US I believe, especially in light of the First Amendment’s protection of free speech. Google, Facebook, and Twitter have even already been criticized for alleged ‘censorship’ of political content/advertisements that are not in line with the platform providers’ ‘political bias. Of course, Trump outed this criticism (https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2019/06/26/trump-signals-us-government-should-be-suing-google-facebook/), but Democratic Party Presidential candidate Tulsi Gabbard even went to actually sue Google for it (https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/25/technology/tulsi-gabbard-sues-google.html). It goes to show that ‘censoring’ (political) search results and rejecting advertisements is a very controversial step to take as a platform-providing company.

Also, look at the scrutiny — even legal action — against Google’s subsidiary, YouTube, for its content filters: https://www.wired.com/story/no-ones-happy-youtubes-content-moderation/

The problem with answering the question that Ronald van Velzen has posited, namely whether search engines have a responsibility to offer users the most relevant content, is that we first have to examine what the role of a search engine in today’s society is.

Yes, search engines are owned (in most cases) by private entities that have a fiduciary responsibility towards their shareholders. Shareholders want the company to continue growing in profitability and size in order to increase their own profits. If we think of the function of a search engine as purely a service from which consumers can pick and choose, there is no problem with the fact that certain (if not all) search engines omit relevant content when it leads users to competitors. After all, Google got big because it just gave the best results, so if I can get better results from another search engine because Google started censoring their content, I will just switch, right?

However, in the cases of Baidu in China and Google in most of the western world, although alternatives exist, most of the general public is either not willing or not informed enough to use these alternatives. This then means that a large percentage of the general public will miss out on certain information that might be relevant to them.

These situations are close enough to the monopolization of the search engine market that governments should consider either breaking up these companies (which I personally don’t see as a solution) or introduce legislation that expressly states that no filtering on the basis of competition may occur.

The same debate is also ongoing regarding Facebook’s new “News” section and even before that when many users saw Facebook as their one and only source of information. There is legislation in many countries wherein rules are provided about fact-checking and truthfulness concerning the content of ‘news media’. This ‘news media’ has long been described as those companies that ‘make the news’, for instance, cable news, newspapers and other entities that pursue investigative journalism.

The debate has now shifted to the question of whether to include platforms such as Facebook and Google News, whom do not ‘produce’ the news, but rather function as an aggregator and sharing-service.

In recent years both these services have ‘self-regulated’ because of negative attention and consequences of their lack of regulations. This can also be regarded as attempts to avoid legislation that might include them in the category of those ‘news producers’. At the same time, Facebook creator Mark Zuckerberg has gone on the record saying he wants more legislation, although a cynic might say that statement was made to boost public opinion of the company.

If you want to read an introduction of how American lawmakers are now finally getting to the actual process of legislating these companies, this article might be interesting:

https://www.theverge.com/2019/8/1/20749517/social-network-legislation-hawley-privacy-research

I personally feel that with the amount of power over public information that these companies have, legislation is necessary to ensure that the rights and needs of the users (and therefore citizens) are placed above the rights and needs of the companies.

It’s interesting to see these efforts by US lawmakers to legislate digital news/search engine/service outlets. Better late then never I suppose; an inevitability if you consider the reactionary nature of the politics of today in dealing with an ever-advancing tech-branch. I agree with you consumers (of these digital services) should have their personal data protected. However, merely clicking “yes” on a prompt, which is now necessary in the case of cookies (search/adverstising shaping personal data) in the EU, might not be so effective in ‘protecting’ personal data as was intended.

Then again, personal responsibility, like in choosing which search engine services one uses, seems to still be key in data protection of users in the status quo, even with the new regulation in the EU. Partly because even if companies/organizations/governments bare (legal) responsibility for user data, they themselves do not always have the means to get a clear grasp of data flows. The complexity of these flows might necessitate coordinated responsibility between multiple actors in the digital networked society. According to this paper on this topic, this would be most complex and there is thus still much ambiguity:

https://www.jipitec.eu/issues/jipitec-10-1-2019/4879

I think in terms of this type of digital feudalism, Europe is not far behind from East Asia. Even though we do not (yet) have large platforms providing and capitalizing on types of payment services, like Alibaba’s Alipay and Tencent’s Weixin, we only have to look at Google to realize how close we really are. As Bruce Schneider notes in his post about digital feudalism, once we start using Google’s services we are pretty much locked into the entire ecosystem and our daily lives and maybe even more so our professional lives are becoming dependent on this. Take away our Google Docs (especially for us students) and our Gmail accounts and we will come to a standstill. This concept similarly applies to Amazon who is bringing us closer and closer to a point of no return with the voice assistant Alexa. We might think we are careful with our privacy but this article shows otherwise as Amazon recently acknowledged that it employs people to listen to a number of interactions that people have with Alexa.

https://edition.cnn.com/2019/04/26/perspectives/amazon-echo-listening-alaimo/index.html

What’s more shocking is that companies listening to our private conversations are not even that shocking to us anymore as Apple’s Siri controversy took place earlier this year as well and despite controversy, no real change has taken place. I think the real question we have to honestly ask ourselves is what is more important to us, privacy or convenience?

It seems convenience is winning this debate (at least, so far). Facebook’s Cambridge Analytica scandal last year stirred debates on to what extent people were willing to sacrifice privacy. Though at first some people did delete their Facebook accounts, in a society where everyone is connected to the internet and the human need to feel part of a larger community continues to exist, little has actually changed. And that goes for Facebook itself too. The Guardian did an interesting article on this: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2019/mar/17/the-cambridge-analytica-scandal-changed-the-world-but-it-didnt-change-facebook

I guess humans have become so reliant on the convenience such platforms bring to their lives, they are willing to accept privacy violations.

I agree convenience is most certainly winning the debate in terms of a mental trade-off we perceive between what we give up in order to gain something else. More importantly, I mentioned before, that overtime we become apathetic to the violation of our privacy we experience, but even for me on this note, I’m not sure where my privacy begins and ends. I’m sure many of us share a lot of lives online to our friends or everyone, yet to some, this still violates a certain degree of privacy. And this is probably what corporations target as a way to further blur and complexify the porous borders of privacy.

This is a very prominent question in the age of digitalisation. It is often argued that privacy is incompatible with convenience. However, the following article published in McKinsey Digital discusses how successful companies manage to deal with the issue:

https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/mckinsey-digital/our-insights/is-cybersecurity-incompatible-with-digital-convenience

It talks about the importance of finding the right balance between convenience and security for customer segments, which successful companies achieve by “tailoring the digital experience to provide easy authentication while still valuing customer security.” The solution of the problem demands the shift in companies’ thinking about digital experience, security, and transition from a one-size-fits-all approach to a more in-depth understanding of the actual customers’ thinking about security and convenience.

I think that the article definitely shows how it is becoming more important for companies to take control of their own cybersecurity issues and really understand their customers preferences in finding a balance between security and convenience. I think in addition what is also important, is for the government to play a bigger role in educating the population about cybersecurity through national campaigns and courses at schools. I think in order to be more cyber secure and more aware of when we compromise our privacy and if we’re okay with that, we need to look not just at the big companies but also to ourselves. If we become more educated on this topic from a young age, we can make better decisions about our privacy and how to handle our data which will lead to a more secure and digitally apt society.

Today, our highly advanced digital societies automatically assume that anyone can tune in with a digital device. And so, payments are mostly done digitally, and other commercial services also greatly depend on their online applications. However, with all these everyday online interactions through digital services our lifestyles and interests are gathered and algorithmically become explored. Personally, I do not believe that this ‘platformatisation’ is a temporary state of the digital age. Digital feudalism depends on profits and competition and by gradually making services only accessible online, consumers are ‘forced’ to resort to online platforms. And so, the mass market can interplay on personalization by interaction. Nevertheless, it is safe to assume that digital feudalism will advance further and that platforms’ profitmaking of algorithms will not remain the exact same as it is now. There have been discussions on the matter of privacy, which will most likely continue and shape (for some part) the digital advancement. But, change is inevitable as access to technology and widespread open knowledge leaves room for the emergence of new paradigms. And as information is so readily available to internet users through everyday online platforms citizen entrepreneurship will continue to rise. These citizens will most likely focus on employing online means to cater to local communities and therefore online platforms arer ever changing in new directions.

Interesting comment. As you say, because of ‘platformatisation’ and digital feudalism consumers are more and more forced to resort to online platforms and platforms will be making profits off our data. Do you think it is possible for these online platforms to expand on this concept and change into new forms without harming our right to privacy?

I think concepts and terms like privacy are ever-changing, perhaps our range of sensibility to privacy changes depending on how much exposure we get to slow – long processes of new forms of platformisation. I would like to reiterate Gramsci’s point on power and consent, because lets all agree that much of this is a platform for power relations to play out, and thus, unless we are revolting and disagreeing completely, even remaining apathetic and silent about small infringements on privacy is consenting to this new form of discursive power. https://www.powercube.net/other-forms-of-power/gramsci-and-hegemony/

It is interesting to note how the government of the Netherlands perceives the future of online networks and digital network platforms’ dominant stance in online competition. Check out this letter on “Future-proofing of competition policy in regard to online platforms” : https://www.government.nl/documents/letters/2019/05/23/future-proofing-of-competition-policy-in-regard-to-online-platforms

That is indeed an interesting letter, it illustrates nicely how it might be difficult to apply regular laws to the digital environment. Moreover, I think it is interesting how the letter on the last page concludes that the Netherlands would be unable to achieve any of the desired changes with regard to healthy online competition, by itself. It highlights how in an age of border transcending digital platforms, we need to have policies that apply beyond the borders of nation states, as especially smaller nation states are no longer able to successfully enforce laws as they would deem desirable.

In an effort to strengthen market positions, both Kakao and Naver have announced new ‘user service upgrades’ (see http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20191009000190&ACE_SEARCH=1 ) . Naver’s update focuses on social influencers: “With Naver’s new service, when its users search for something, social influencers’ video and image contents would show at the top of the results. The service will start from 200 keywords related to beauty and travel.” This will surely have a huge skewed impact on search engine results in favor of major influencers and the brands that advertise through these influencers. I personally believe this is not a desirable development. What do you think?

I think this is weird more than anything. Creating an ecosystem purely in favor of artists and creators is certainly an interesting idea but I can only imagine that as you said, search engine results will be incredibly skewed and there will be a massive difference in results.

I think it is a good idea when it is used as an option/personal preference that people can opt-in and out of to get more personalized search results if they belong to the target audience that actually wants to get influencers and artists content and recommendations to be prioritized. However, this certainly does not work for everyone and to suddenly change the search engine’s algorithm is not desirable as a lot of content will not be displayed as most relevant.

I agree with Esther that it could be an opt-in and in that sense it is interesting. If search engine platforms are transparent about the mechanics behind their search engines, I personally don’t see an issue. If you don’t like the mechanic, you can opt for another search engine that hopefully does fit your desired needs. Transparency of these companies would be key in this case.

Concerning this point, I would like to reiterate one of Knight’s (2014: 237) concluding remarks, namely that:

“Designing search engines is a hard challenge; many searches are ‘precision’ searches aimed at the recall of an individual token, but many others, such as holiday planning or weighing

scientific literature, involve ‘exploratory’ activities and credibility judgments of sources. Thinking about how best to represent results for these multiple purposes is complex.”

Thus, once these intentions are clear, and these specific search engines work as they intend to do, we could still question how effective they are in attaining their intended goals.

http://networkcultures.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/SotQreader_def_scribd.pdf

How is the digitalisation in Asia different from the rest of the world? And if it is, what is so unique about its digital spaces and practices?

Gregor Theisen (managing partner of McKinsey Digital in Asia Pacific) highlights three features of the Asian digital market. First, it is around innovation. Second, is how they leapfrog technologies. The level of social network penetration is very high. This creates new opportunities and facilitates the development of unique business systems and digital ecosystems. Third, it has to do with people’s openness to new technology. The third point about consumer open-mindedness is even used to explain China’s success of digital market.

https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/mckinsey-digital/our-insights/digital-innovation-in-asia-what-the-world-can-learn

Very interesting piece. I find it quite profound that the acceptance of consumers is so focused on. It raises questions of politics, culture, and economy above all. What’s even more striking is that these characteristics I personally do not feel like is specific to simply an “Asian” experience, rather it all really comes down to a willingness to accept change and willingness to accept new products for consumers. Although I do not believe this is “Asia” specific, it really raises the question of why markets globally have not pursued these endeavors similar to the examples mentioned in the articles. Thus posing questions about Consumer Culture in region-specific experiences. Refer to this article to delve deeper: https://www.straitstimes.com/opinion/the-good-and-bad-sides-of-consumerism.

…Perhaps it is also pivotal to keep in mind the many articles on these topics as belonging to a great corporate agenda. The agenda of promoting certain cases for the benefit of McKinsey themselves, it thus becomes a platform for power relations and forces us to re-evaluate certain points that are typically seen as “occurring only in Asia.”

The meaning of convenience is constantly changing as we see the development of new technologies and what they can offer us. Check out Christoph Berendes’s article where he describes his experience of shopping in the digital convenience store, the newest Amazon Go in Seattle.

https://www.brand-experts.com/distribution-excellence/digital-convenience-store/

Indeed, perhaps later down the line when it is possibly too late, we might deem an extreme opposite reaction to preserving our privacy for convenience. In this article: https://www.theguardian.com/your-local-post-office-partner/2019/feb/12/staying-relevant-in-the-digital-age-lessons-from-post-office

I recognize the prominence for people to hold on to face-to-face connection, and need to avoid cashless society. Is it plausible that this can remain so in a consumerist culture? Perhaps, we simply do not have the resources to combat the ever-changing nature or ‘platform’ of consumerism in today’s day and age

The fears to be left on the outside and become irrelevant in the age of digitalisation motivate businesses to adapt to global trends. This eventually raises the question of exclusion. As Ian mentioned there are people who are not ready to give up cash or face-to-face communication just yet. The increasing digitalisation of life makes us think whether everyone has the same access to technological benefits (not even the digital divide between different counties, but the gap within a country). The consumerist culture facilitated by digital technology indeed leaves little room for the more traditional practices.

Totally agree with your statements.It is interesting to see how some political parties in the Netherlands also play into this fear of digitalised payments such as the 50 plus party in the article below. https://50pluspartij.nl/actueel/2847-cash-pinnen-contant-geld-januari-2019

I think the 50+ party is only saying this for voter revenue, as they have been playing this shtick for a while now. Remember that Henk Krol once got fined for hacking, only to prove a point back in 2013. https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2013/02/15/henk-krol-krijgt-boete-voor-hacken-a1437224

It is clear how deeply ingrained digital culture is in our everyday lives; it is part of every-day culture. In Japan, ‘digital practices’ have come to constitute every-day interaction, between youths most prominently. Adding someone on LINE or Facebook in some ways even seems to be embedded in the act of introducing yourself. You could say this is particularly Japanese, where self-introduction is a prominent part of culture. In a sense, digital platforms seem to become new forms of ‘meishi’ (lit. business card) culture. Thus, digital platforms are merely adopted in ‘traditional’ culture, which is to say both are not mutually exclusive.

‘Mobile’ culture has long been part of Japanese culture, arguably for the longest time in the world. Practices derived from this ‘culture’ are interesting to note — how we should judge them is in contention. If you are interested, an analysis of these practices in Japan have been covered in this book chapter ‘Youth, social media and connectivity in Japan’ by Takahashi (2014): https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057/9781137029317_9

This is indeed very interesting. Moreover, LINE is (becoming) increasingly popular in East Asia, especially in Japan and Taiwan. I think their power and market position will only become stronger in the near future. The LINE app has all the mechanisms in place to stimulate users to keep using the app: as you mentioned, adding someone on Line as part of self-introduction, (as argued earlier today) the fear of missing out on things when abandoning the app, but also the commercial side of the app is doing a great job to bind users. For example, buying new stickers or give friends stickers as a present is quite common to do in, for example, Taiwan (from my experience). I am curious how LINE will evolve over time and how powerful this platform will be in East Asian societies.

I’m a bit late to the party, so excuse me if this has been said before, but it kinda seems like there is a lot of negativity in this discussion regarding digital convenience. It almost seems paradoxical that convenience leads to fear. When googling this question (yup, aware of the irony in this context) there was surely a lack of positive articles. However, we do not reject this culture of convenience. This article https://bit.ly/2MTnt5L argues that digital convenience is ingrained in the minds of Gen Z, and this generation is our future after all. How can we all agree on the dangers of digital convenience but at the same time embrace it willingly?

Good point. I would argue that convenience by itself, digital or not, is often beneficial. Convenient digital platforms provide us with a wide variety of services that most of us would not want to live without. This is all fine, until such services become too dominant and able to influence even our political processes. E.g. google could influence elections in countries by altering its search results. At this point there might be reason for people to cut themselves loose from google, but such a company usually has people entangled in the many different services that they provide. Thus despite being aware of the potential dangers, making it difficult to do anything but complain without putting their money where their mouth is. In addition, with one’s interests at stake it would be easier to believe the likes of google when in such instances they assure they would never do such a thing as influencing elections (while not denying that they would be able to do it).

https://fossbytes.com/how-google-influences-elections-in-your-country/

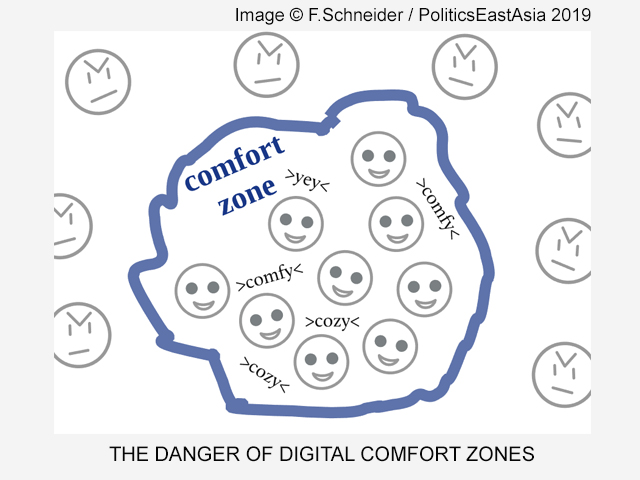

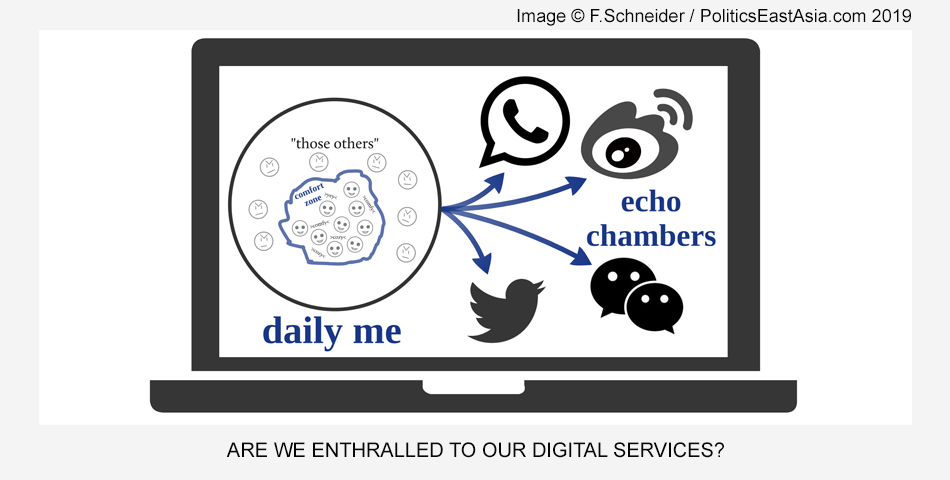

I think an interesting explanation for digital convenience, and especially the rise of so called echo-chambers could be the environment in which children have grown up in the last decades. Some argue that children have lost the “right to roam”, and to explore the outside world (including opinions). Consequently, young people – especially in the West – may grow up with a lack of experience in dealing with worldviews and opinions that differ from their own. Following this line of thought it could be argued that such echo-chambers would be most popular among younger internet users, something that would be worth looking into.

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-462091/How-children-lost-right-roam-generations.html

From personal experience and perspective and the aforementioned article I assumed a link between young people/generation Z would mostly exist in the West. But, perhaps even more than children in the West, Chinese children born under the ‘One Child’ policy, might be averse to different opinions, as well as especially set on instant gratification. These children are often referred to as ‘little emperors’, as they are apparently being raised with excessive care and attention, which would be detrimental for their emotional development.

While there are a fair amount of articles available on this ‘little emperor’ effect, the idea – while interesting as an explanation for issues such as the rise of echo-chambers – might have to be taken with a grain of salt. As there is as of yet not a lot of research that supports it. Although a publication by Cameron et al. (2013) does argue that children born under the one child policy are “significantly less trusting, less trustworthy, more risk-averse, less

competitive, more pessimistic, and less conscientious individuals”.

https://catholicexchange.com/has-the-one-child-policy-spoiled-chinas-children

https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/one-child-policy-chinas-army-of-little-emperors-8446713.html

Cameron, Erkal, Gangadharan, & Meng. (2013). Little emperors: Behavioral impacts of China’s One-Child Policy. Science (New York, N.Y.), 339(6122), 953-957.

For anyone who haven’t seen this clip yet, I’ll just leave it here: https://youtu.be/SE_ccFHjL_w It’s John Oliver’s view on the little emperors (or little meatballs specifically). He points out that thousands of women get abducted to serve as women to these meatball-men. And this is where I’d like to connect it to your echo-chambers and where the internet get’s freaky: the fact that men literally think that you can just “buy” wives, and make them your property. This led me to googling China’s incels (involuntary celibates), I found out that there’s actually a branch called “ricecels”. I encountered very racist websites and subreddits (and sorry, I will not post them here) and boy, the internet does become a nasty place outside of your own little, cozy bubble.