Digital Nationalism, Digital Territory

A Discussion with Students at Leiden University

Much speculations has surrounded the future of nation-states. Challenged by neo-liberal globalization and by advanced information and communication technologies, it may at times seem as though the traditional world of nation-states is making way for a more transnational world. Yet national movements seem alive and well today. This raises the question of whether globalization optimists are greatly exaggerating the death of the nation. How do nations and nationalism really connect to technological developments, and what can the case of China tell us about these dynamics?

As part of our Leiden University seminar on the politics of digital China, I have asked our graduate students to discuss how nationalism, a modern sentiment that has its roots in the European Renaissance, fairs when societies update it for the information age. The East Asian region is a particularly relevant place to look for answers to this question. Classic issues of (inter-)national politics such as territorial disputes remain matters of great concern in the region, as continuing tensions over islands in the East China Sea amply demonstrate.

The dynamics that drive such tensions are no longer dominated solely by national governments: private enterprises, non-governmental organizations, and individual citizens all engage with government actors to shape what the meaning of ‘national territory’ should be (cf. Denemark & Chubb 2015). Much of this dynamic plays out on the internet. International relations are thus today often influenced by non-traditional actors, especially those who are able to push or manipulate public opinion online. This was particularly evident in 2012, when Chinese, Taiwanese, and Japanese claims to the so-called Diaoyu / Senkaku Islands elicited strong emotional responses from connected publics that framed how politicians in these countries reacted to the dispute.

In a country like China, which lacks electoral mechanisms at the national level that might create feedback loops between the governing and the governed, it remains a much contested question whether (and how) such public sentiment about foreign relations might affect foreign-policy making (cf. Gries et al. 2016). If there is indeed such a connection, is it then more accurate to think of the Chinese leadership as a group of rational actors who cleverly manipulate public sentiments for their own purposes, or is it more appropriate to view popular opinions and protests as informing elite decision-making?

Join our debate about digital nationalism below, in the comment section, and share with us your views on how territorial conflicts and the influence digitally-enabled publics have on international relations in the East Asian region.

References

Denemark, David & Chubb, Andrew (2015), ‘Citizen Attitudes towards China’s Maritime Territorial Disputes: Traditional Media and Internet Usage as Distinctive Conduits of Political Views in China’. Information, Communication & Society, 19(1), 59-79.

Gries, Peter, Steiger, Derek, & Wang, Tao (2016), ‘Social Media, Nationalist Protests, and China’s Japan Policy: The Diaoyu Islands Controversy, 2012-13’. In De Lisle, Jacques, Goldstein, Avery, & Yang, Guobin (eds), The Internet, Social Meida, and a Changing China. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press (pp. 161-179).

Share This Post, Choose Your Platform!

41 Comments

Comments are closed.

The two can be true simultaneously. Sentiments are encouraged and guided, but develops a life of its own within the public discourse. CCP now has to answer to their own propaganda?!

An option the CCP chose not to take was to prevent the protests from happening at all. But allowing these protests is not without risk for the CCP. It’s a useful diplomatic tool so why not use it, but at least from the perspective of Western media outlets, the protest itself seems to be heavily orchestrated to ensure it doesn’t get out of control.

http://www.nytimes.com/2005/04/15/world/asia/china-is-pushing-and-scripting-antijapanese-protests.html

I agree. When government speaks, they will say “people believe”. Actually, conflicts between people and citizens take small proportion, that is about legitimacy and scandal of governance. When gov kicks off inter party or deals with corruptions, science/tech, it is informed well rather than manipulative. CCP knows how to buy over people’s heart.

Nationalism propaganda fundamentally follows process of sender-content-receiever with mass media (CCTV News Report, politics study on each Wednesday in planned-economic times, etc.) and patriotic education. Dept of Publicity has a routine to express “people’s voices” to authorise executives. Manipulation is then formed between gov to citizens that people unconsciously support routes of state and Party’s leadership. People at least in my life social circle know the manipulative relationship and some of them are “conspiracy theorists” who keep on suspecting Dept of Publicity, principles in Politics textbooks, etc.

Diaoyu island, South China Sea cases are beyond the manipulation because those were ignored in propoganda lists unlike Taiwan Province. Then, people as receiver have space to make “critical” thinking and they respond to the missing propaganda of the government in the past. Those statements can be, for example, the rise of China show the strength to win it back; Poor government in the past was only aware of land sovereignty, etc. What I would like to argue is the fluid of national strength and ineffectiveness of propoganda results in possibility of people responding and informing the central government. And public opinion is then “selectively” accepted by the gov. Quoting net users’ blogs or making interviews on CCTV becomes more frequent and convincing.

“Person with conch speaks (Lord of the Flies)” Contests happen between state and people, manipulation and informing, as well as international relations. When strength contest is as clear as it exists between stone and egg, then everything is easy to see. But nationalism though monopolised and manipulated by gov occupy (mostly) is fused with historical aspects and hope of nations. It is a product of sentiment with factual tools.

The following link is about national war that people are often inclined to advocate in those inter-national conflicts. Although people thinking of war seemed funny and ignored many essential international relation factors, digital territory draw imagined community which shares recognitions of state, nations, and Chinese races, etc.

http://nationalinterest.org/feature/3-ways-china-japan-could-go-war-13202

Couldn’t it be the case that the government still manipulates people even in the Diaoyu case? Not only by having spread information through traditional media for a long time, but the government might also let people think they are being critical. People might think they are influencing the government but maybe that’s just part of the plan. Even if the government did not anticipate protests, letting people believe they are influencing what the government might be a convenient response to this rather than trying to stop protests. That doesn’t mean that the government is actually being influenced by these protests or that it resorts to more military strategies because of it.

Creating the fraud of people informing cost much and do not necessary. At many aspects unrelated to legitimacy and wrong choices of governance (several in the past), gov has no need to lead them, because Chinese people are more educated, familiar with CCP’s propaganda. Many China’s areas was forgetten to live and govern, especially for maritime territory. Without international trades in the past, sea is only sea to China.

I think the struggle between the people and the government over who is influencing whom is a negotiation always in process. As we have seen with the censorship, it can be argued that the government negotiate with internet users, writers, journalists, and so on about what can be said. This process is characterized by contunuing challenges which see the actors struggling over the limits they can reach in their public expressions. I think it is the same for the case you mentioned. Both the people and the government are influenced by what the other group’s members do and, especially, how they react to certain strategies played out in public discussions. Online it is a bit more difficult to differentiate who is belonging to what group and who is influencing who. Nevertheless, the influence direction is not one-way but bi-directional.

Your ideas are well said, yet I’m thinking further from bidirectional to constellational. The integrated information theory of consciousness (iitc) as presented by Tononi (2012) would cpntectualize this well. Tononi would have us ask, to what extent does a system have consciousness? http://bmcneurosci.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2202-5-42

The Government clearly understand the importance of guiding public opinion. I think it’s effective because it’s this potent mix that Callahan talks about when he calls China a “pessoptimistic nation” It’s this – China is on the right track to be number one, and there’s a genuine sense of pride about the country, mixed with this “oh but we are so weak and bullied” – that actually makes it so a powerful rhetoric.

I think that the Government does get influenced by public opinion – that they are part of the same dialogues and meaning making process. The need for propaganda and the correct historical narrative (martina below) shows that they think that public opinion is important, so it shouldn’t be dismissed as a convenient excuse for letting Chinese people think that they are participating —- by doing this we are dismissing people’s anger as a product of brain washing. The problem with the quantitative analysis that has been done – it doesn’t engage with nationalists, it doesn’t try to understand the meaning they attach to protesting as an act.

http://www.thechinabeat.org/?tag=chinese-nationalism

Also

http://sinosphere.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/09/24/china-nationalism-jessica-chen-weiss/?_r=0

Well, if you compare two very different reactions regarding Diaoyu/Senkaku islands dispute in 2012 and International Court ruling on South China sea in 2016, it is clear that Government’s reaction to nationalistic uproar was different, as no major protests happened and overly nationalistic comments were more rigorously deleted. It seems strange, that all the people, that protested in 2012 would miss opportunity to protest against “hurting Chinese feelings” on such a high scale. I think there is no doubt, that 2012 protests happened because someone “behind the curtains” wanted for it to happen, while in 2016 they didn’t.

But it must be pointed out, that both Government and CCP are by no means homogeneous. There are different factions with different goals and interests as well as political views struggling for power. This article, for examples argues that Jiang Zemin faction was behind the scenes of Diaoyu Islands protests, in order to cause trouble for Xi Jinping’s ascension to power. Even though pro-Falun Gong media is infamous for its anti-Jiang Zemin biases, and not everything should be taken for granted, but their interpretation could as well be, at least partially, true.

http://www.theepochtimes.com/n3/1481936-chinese-leaders-dismantle-jiangs-last-bastion/

South China sea could arguably not muster the level of nationalism that Diaoyu islands does, because it is an argument with the philippines and maybe the Hague international court (if that’s the case you are talking about). Diaoyu Island resonates with the people because it’s Anti-Japan, and it represents Japanese Imperialism and aggression.

I hadn’t thought of whether it could be political factions though. I’m not sure that makes sense to me though, the Diaoyu Islands protests did provide the China-negotiating-team with a bargaining chip, (i stopped knowing which actor to use) I think that’s why they let it, and possibly even encouraged it. Judging by reports, they made sure it was under control though, which shows that it is a risk.

It it difficult to measure effectiveness of whether people’s protest and government’s determination. Usually, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs only “strongly condemns”. This depiction always receives much laugher among Chinese. As I said, real struggles are embedded in economic policies, competition in international relations, etc.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs statement is attached, a good material for discourse analysis.

http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/topics_665678/diaodao_665718/t968188.shtml

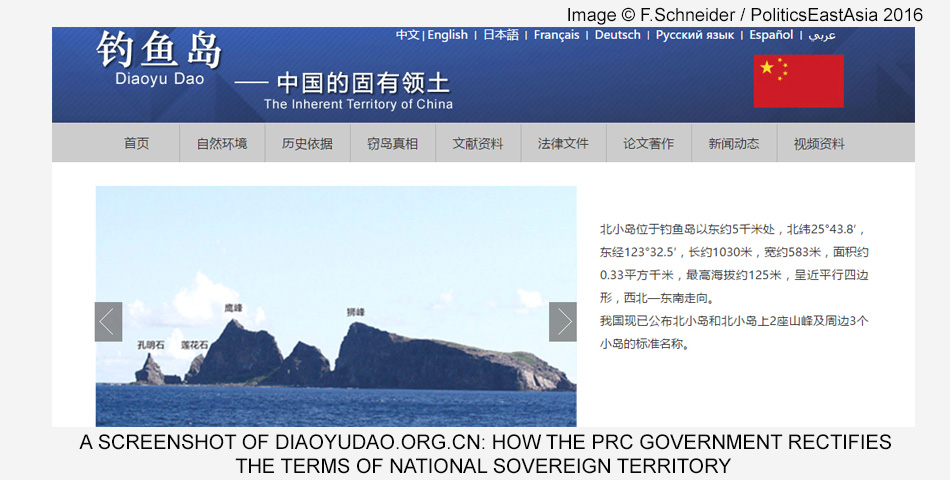

Technological developments have made possible digital platforms for citizens to discuss matters that are related to the imagined community that is a nation, and further the territorial envisioning of a nation-state as shown in the case of the Diaoyu Islands, Schneider has pointed out, in his research on how symbolic and discursive resources on China’s web frame the political developments in the East China Sea, that several actors play a role in the discourse of the Diaoyu Islands. Schneider further points out that the amateur groups that contribute to this discourse are often taking radical stances and making authoritarian claims. As Schneider has noted, this may not represent popular sentiments in China.

I agree with these views, as one can imagine that in discussions, those who are heard the most are the loudest discussants. They may have reasons for being the loudest, either having stakes in the matter discussed or taking an interest in the matter. This may be even more so the case in discussion that takes place online. A setting of discussion online is different than offline as one does not know who the audience is or will be in the future and further is dependent on the structure of the platform of discussion. The engagement in discussions on certain platforms regarding territorial disputes are requiring one’s effort to search for platforms that are discussing these matters. (to a certain extent this is less the case for social media, such as Facebook, where newsfeed and discussion of online friends may be automatically come to one’s attention). My point is that on particular platforms which are specifically designed to discuss such matters, may attract a more homogenous audience, as people are more likely to engage in discussions where they take interest.

If such is the situation, then perhaps it is fair to say that this can be beneficial the Chinese leadership in manipulating public sentiments, and less appropriate here would be to say that such discussions are meant to inform the elite as the audience is not representative of the popular sentiments.

in addition to this I would like to mention that a rather homogeneous group of discussants on online platforms, if strong enough, may have the effect of creating a social movement/nationalist movement, which are not necessarily representative of the sentiments of the Chinese nation as a whole, but the specific interests that binds them, may make them a more important group for a government to listen to rather than the ‘mainstream’ mass which could have divergent stances on matters as territorial disputes.

when searching on google for online social movements i found this research which conceptualizes the social movement online community

https://uncch.pure.elsevier.com/en/publications/a-social-movement-online-community-stormfront-and-the-white-natio

the researchers Caren, N., Jowers, K., & Gaby, S. collected data from a nationalistic online social movement (and racist movement..ahum..), this is their website (I wasn’t surprised by the existence of such a platform, but it turns my stomach)

https://www.stormfront.org/forum/

for those interested (hopefully pure academic interest), I found that this website is largely closed to those who are not members of the community and have accounts, but the links that are open to ‘guests’ contain among others this one https://www.stormfront.org/forum/f14/ where there are discussion on the holocaust and fake hate crimes T_T

back on topic, I can imagine that such a community as that of stormfront would not have been possible in its current form (and size) if it wasnt for technological development.

Relatated to what you have written, I was also looking at online patrioctic/national groups. These are some articles related to the Little Pink(s) (小粉红). The first and second aritcle are also related to the presentation we had in class on Egao (it refers to the ‘Diba’ case).

https://cpianalysis.org/2016/09/22/translation-in-activism-and-cyber-nationalism-in-china/

http://www.sixthtone.com/news/keyboard-crusaders-train-sights-bigger-issues

http://chinadigitaltimes.net/2016/08/little-pinks-new-face-chinese-nationalism/

There is also an Internet nationalist group called Voluntary 50 Cent Army, which originated from genuine pro-CCP nationalists being mistakenly labeled as 五毛, but is entirely different in essence from them. I think it is interesting case how unjustified name-calling contribute to creation of new group identities.

https://cpianalysis.org/2016/02/29/the-voluntary-fifty-cent-army-in-chinese-cyberspace/

There is a Chinese idom: wu he zhi zhong meaning mobs. It is a must have right and wrong and an appropriate approach. But CCP’s propoganda is indeed not regarded as effective as liberal doctrines in America. Even Chinese know it is more a failure than success considering cost it takes. Buying people’s hearts is anyhow an effective methods. Aparting from polls, nationalism sentiments is indeed interesting to study in China where everything is extremely unbanlanced. How is this doctrine made that consistent?

I think that nationalism is very much alive in all the countries and it is in the countries governments’ interest to maintain nationalism alive. How do they do so? In many different ways; in China it has been argued that one way to foment nationalism is through the vision of history as a shrine. We have already discussed in class that Chinese history, especially the modern history, is characterized by being a monolithic version, a singular version of historical facts. When this version is contested by historians, it is common to see their voice being silenced. One pertinent example, that also relates to the discussion around the contested territories (such as the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands), is with regards Tibet (sorry to mention everytime Tibet, but I am currently doing research on it and I have more examples related to Tibet rather than other territories). The history of Tibet is contested between the Chinese central government and the Tibetan government in exile; the versions the two parties defend are obviously very different and both are enforced with national melodies. This strategy, used by the CCP, let Chinese people personally feel a sort of ‘attachment’ with Tibet. People start to feel the necessity of Tibet being and always had been part of China. This strategy resonates in more or less subtle ways in the Tibetan territory. For instance in Tibet almost all the houses (especially the Tibetan traditional houses in the small villages) wave the Chinese flag on the roof (when I was in Tibet I was surprised for the huge number of Chinese flags in these isolated villages in the middle of nowhere!). Another way to enforce nationalism is certainly propaganda. This is a nice article that illustrates how, with the help and the ‘grace’ of Chinese liberating Tibet from serfdom, now Tibet is a prosper territory which has a brigh future ahead. http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2016-03/27/c_135227725.htm

So far I have pointed out the way in which nationalism can be deployed to confirm and reinforce a version of history that is the one which legitimates the CCP. With regards the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands I think the CCP’s attitude is almost the same to the one carried out with regards to the territories asking for independence or more autonomy such as Tibet, Xinjiang, Taiwan and Hong Kong. The different thing is that the public discourse is not addressed to ‘splittists’ or ‘separatists’ who asks for independence from the great mainland China, but it is addressed to foreign countries competing with China for a territory, for example, Japan. This difference reinforce even more the public discourse with nationalistic melodies and the sense of unity of the Chinese people. I agree with what have been said in the previous posts regarding the fact that the nationalistic public discourse online does not reflect thoroughfully the ‘masses’ sentiments’. Rather than that, it reflects a fragment of the society’s sentiments which are homogeneous and aligned with the government’s views on that matter. The fact that there are certain websites designed precisely to discuss about certain topics such as Diaoyu/Senkaku dispute or what we previoulsy have read about, the Nanjing massacre, will probably determine the kind of audience who participate in the discussions going on in these websites. Moreover, because these websites are set up most of the times with the approval or contribution of governmental or para-governmental institutions, it can be said that these discussions have more relevance and can be seen more, rather than random discussions on random websites. The point is that, maybe the government does not orchestrate the dicussions themselves, but it probably orchestrate the space in which these discussions can or cannot begin. The government therefore set up websites that convey a certain image or version of a dispute (images or videos are often deployed in order to let the version defended be more legible and immediate to the receiver) and, in this way, it leads and guides the beginning of the discussion in a certain direction.

You are right, I haven’t seen as many Chinese flags as you mentioned anywhere in China outside Tibet. This reminds me of something I would call ‘nationalistic overcompensation’. In Chinese Government discourse China’s contested territories are often referred to as “sacred”. Somehow Diaoyu islands, Tibet, Xinjiang, Taiwan, South China sea are China’s sacred territories, something that is never said about Shandong, Hubei or Beijing. For example, Chinese embassy of Lithuania:

http://lt.china-embassy.org/eng/

3 out of 7 banners on the left (in the most visible part of the website) are about Tibet and Xinjinag. If really there is no doubt about their belonging to China, why to single those regions out, why there is no information about non-politically sensitive areas?

There is also overcompensation in putting “China” in front of Taiwan or Hong Kong in the most bizarre ways. I once saw an interview on CCTV when with one Chinese celebrity where she said: “I went to Beijing, Jiangsu, Taiwan, Guangdong (我去了北京、江苏、台湾、广东)”, while in the subtitles it was transcribed as “I went to Beijing, Jiangsu, China Taiwan, Guangdong” (我去了北京、江苏、中国台湾、广东)

Don’t you think that these “Freudian slips” of over-propaganda can actually have opposite results than anticipated, since realization of smallest logical inconsistencies could destroy trust in whole CCP rhetoric in general?

This ‘nationalistic overcompensation’ is something I also encountered when writing my BA thesis. For my thesis I looked at a number Chinese tourism websites and they would often have a section devoted to the ethnic minorities or territories. In these sections you could find all the different ethnic minorities or territories and information about them.

What I found was that articles related to minorities/territories from Tibet/Xinjiang would always contain vastly more information than other minorities/territories. The articles would even go out of its way to emphasize how they have always been part of China and how, for instance, the Tibetan people have been ‘liberated’.

This way, they not only overcompensate towards a domestic audience, but also towards a foreign audience.

The website: http://www.cnto.org.au/component/content/article/81-about-china/the-people/145-ethnic-tibetan.html

Yes. Besides tourism, there are many small restaurants and Sunna places naming Diaoyu Barbecue or Daoyu Sunna. Commeral opportunity is another reason to promote popular sentiment because it catches extensive customers eyes with no niche requirement. Also, there are DIY T-shirts printed Diaoyu Island belongs to China in TaoBao shops.

As you both mention the huge amount of Chinese flags in Tibet, I would say that it is fact overcompensation, but also a logical appearance, since the government wants to show that it is their territory. Besides this, don’t you think the Chinese who live there indeed feel that they are Chinese citizens and that they have to show this by national flags and the national anthem? I think it is also a way of exposing their patriotism to the rest of the world, because other countries are also judging the wat China rule over Tibet.

Of course they want to show that it is part of China and there will definitely be Tibetans showing off their patriotism but overall it is telling that they mainly do this in territories that are more contested, you don’t see this kind of extravagant patriotism in other provinces in China like Jiangsu or Zhejiang that do not have the amount of territorial disputedness as, for instance, Tibet

Here is a nice article about Digital Nationalism in China.

http://chinadigitaltimes.net/2016/09/backlash-online-chinese-nationalism/

I reported two sentences those I think are important in our discussion.

A state that relies upon nationalism for stability is making use of a fundamentally unstable ideology. [… B]y cultivating generations of xenophobic nationalists as the core of public opinion, the Party has in fact made the prospect of sudden democratisation a scary thought.

Examining this paradox of nationalism in China today, it becomes apparent that any future political change must start from cultural change. This would allow for a wider and considerably more open airing of viewpoints beyond the current politically correct, nationalist perspective. But such cultural change remains highly unlikely so long as a party that relies upon nationalist ideology for legitimation remains in power.

Why is cultural change so unlikely? The rise of the internet has changed the culture and means of activism, which has already enabled a wider range of opinions and expressions being allowed. I think internet culture and what can be said online changes constantly and even opinions that the government isn’t happy about are being posted, so who knows what that will lead to in the future.

I find this very ironic:

http://www.scmp.com/news/china/policies-politics/article/2042784/xi-jinping-warns-communist-party-would-be-overthrown-if

Xi Jinping says:

“The Communist Party would be overthrown by the people if the pro-independence issue was not dealt with.”

This remark shows him being aware of the danger of using nationalism as a foundation of stability. Backing down of any of the issues could easily trigger anti-CCP sentiment.

I am very surprised he would say such a thing. Especially since the whole Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands row, I would expect most senior CCP members to far more cautious about making such bold claims that give them so little room to compromise. Phrasing it this way, he actually opens up an opportunity for people to criticize the CCP and the PRC government if they don’t ‘deal’ with the pro-independence issue.

It sounds indeed like he opens up an opportunity for people to criticize the role of the CCP, but I don’t think it will cause trouble, because I think a lot of Chinese people are very nationalistic, because they fear that when there comes an anti-CCP sentiment that this will eventually lead to a civil war. In the past China already had a civil war and people are still aware of this terrible period of time and don’t want this. So I think this makes the idea of nationalism stronger.

One phenomenon which plays a certain part in Chinese on-line nationalism are Government-paid online commentators or the so called 50 Cent Army (五毛党). Here is a relatively new article about it:

http://www.voanews.com/a/who-is-that-chinese-troll/3540663.html

While there is hardly possible to understand how big their influence is on nationalist debate, it safe to say that they definitely constitute a certain part of pro-governmental/nationalistic comments.

Even though 50 centers do not work very effectively as they lack of motivation and their comments are not as persuasive, the second group, mentioned in the article Communist Youth League is much more subtle and sophisticated. Eventhough Communist Youth League is not exactly equal to CCP or Government, it is subordinate to them, so their activities can be interpreted as State’s intervention into public discourse.

Furthermore their activities are intended to inflame Internet users with nationalistic fervor. No wonder 50 Centers/CYL activities are officially called ‘guidance of public opinion’. Even though it is hard to evaluate how big Government manipulation of public opinion on Chinese Internet is, I strongly believe it is quite significant.

I agree with you that the government manipulation of public opinion on Chinese Internet is quite significant, although I believe the 50 Cent Army is called such negative nickname exactly because they are not government-paid, creating comments that are not persuasive, as you said. The government wouldn’t pay such group of under-educated people to spread nationalism, and because this group of people are not paid to express such pro-governmental/nationalistic view, I believe they are very much motivated. But what exactly is their motivation is worth discussion. I personally believe a large part of their real motivation is to find a way to let out their frustration in real daily life instead of really being a nationalist. By the way, I’m a member of the Chinese Communist Youth League but I don’t feel any difference being in the league. As a matter of fact joining the league isn’t something that you ask to do in Chinese schools. It’s something that your teacher ask you to do. So I think the article should mention that the views posted by the Communist Youth League might not represent the will of the entire league.

Of course, Youth League is not a homogeneous organisation. There are different people with a wide range of interests and political ideas within the group. Same as with CCP. I personally know quite a few not only CYL but even CCP members, who are very strongly critical of CCP, who call Mao a devil and are for democracy and human rights. It is something hard to imagine in the West, but it seems to me that in China affiliation with political organizations doesn’t tell much about person’s political values, for some people it’s just a way to get more privileges and better career opportunities.

Yes. In anti-JP movements, some activists, then were proved intentionally hired by some Chinese auto companies, destroyed HUNDA, Toyota branches in China to maintain local protectionism in domestic market. This led to difficulty to analyse citizen’s nationalism sentiments. There came some “other purposes”, such as commerce, revenge, etc.

This discussion very much puts to my mind the questions of identity. These questions are situated upon contexts and inspections of such considerations as: the individual, various forms of culture, ethnies, history, nation, state, dominance, submission, power, disempowerment, and even the hypothetical emergence of new identities. Of course, some impact exists as a result of the influence of neo-liberalism and information and communicative technologies and the spaces such discourses open and in which people think, be, and exist. I also wonder of the potential of various catalysts to open such spaces where discursive intercourse occurs and how such public and private discourses manifest and might either be maintained or extinguished. It may remain to be studied as to what social, political, and economic ends such affordances give rise to and how catalyzations within these spaces take place. Yet, it seems that optimists may base their interpretations and analyses upon idealisms, while there may remain, specific realisms that will not be ignored.

Another way to look at Chinese digital nationalism is comparing it to digital nationalism in other countries, for instance, Japan, the most important rival and enemy considered by a large part of Chinese population for more than a century. It seems that compared to nationalists on Chinese websites, Japanese “internet right-wingers” have a much smaller scale. Unlike in China, where anti-Japanese thoughts, especially around times like the dispute of Diaoyu / Senkaku Islands, are accepted by a considerably large proportion of common people, even though the fact that Sino-Japanese trade plays an important part in both countries’ trade structure is also widely acknowledged, in Japan, it seems that the “internet right-wingers” are not as popular. Why is it the case? I think one of the reasons might be that in China online nationalists are mainly people from lower classes, while according to Furuya Tsunehira, the writer of the first article below, the “internet right-wingers” are mainly middle-class males. Extreme right-wing thoughts can be accepted much more easily in lower class communities with lower education level. Another possible reason might be the “historical vacuum” in Japanese history education as discussed in the article:

http://www.nippon.com/en/currents/d00208/?pnum=1

Another related articles:

http://apjjf.org/2011/9/10/Rumi-SAKAMOTO/3497/article.html

http://view.news.qq.com/zt2012/aiguo2/index.htm (in Chinese)

Digital nationalism in China isn’t just expressed on territorial disputes. Only this month, another incident happened in Beijing and it aroused outrage on Chinese internet to a boiling point. Rainer Gaertner, president and CEO of Daimler Trucks & Buses China was reported to have shouted at his Chinese neighbours, “I have been in China one year already; the first thing I learned here is: all you Chinese are bastards,” and then attacked them with pepper spray. According to News websites in Chinese, the Daimler Trucks & Buses China has apologised to the Chinese public very quickly on their official website and has removed Gaertner from his office in China. What is interesting is that like on many international disputes happened both on a national and individual level, Chinese nationalist online are once again demonstrating their knack of exaggerating things to make them much more serious than they actually are. This time, voices of boycotting Mercedes-Benz cars can be heard all over Chinese internet. But meanwhile other voices can also be heard, such as taunts like “You want to boycott Mercedes-Benz because you can’t afford it anyway.” This might demonstrate that irrational nationalist comments on Chinese website largely come from lower classes.

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/wires/afp/article-3959926/Daimler-removes-China-executive-racist-rant.html

http://news.sina.com.cn/c/nd/2016-11-24/doc-ifxyawmn9975949.shtml (in Chinese)

About 五毛党 50 Cent Army I would like to say that I do believe government-paid online commentators exist. I also believe that other governments also hire troll army to create comments online even on websites in other languages in order to direct public opinions. As a counterpart of 五毛党50 Cent Army there’s also a group of people online called 美分党 (American Cents Army? I haven’t found the official English translation to this concept yet) who are extremely pro-American/Western. They post comments on Chinese websites such as “Look at them foreign people (to many Chinese common people, foreign=West), they are so great. They have everything better than us.” Whether and how much this kind of comments are manipulated by the Western nationalism I can’t say.

https://goentw.wordpress.com/2016/02/14/%E7%BE%8E%E5%88%86%E5%85%9A/ (in Chinese)

Well, I would completely rule out the idea that 美分党 are paid by foreign governments, because not only there are no evidence, but it would be very irrational thing to do. Can you imagine a foreigner who spends 5+ years to learn Chinese doing that? Considering how rare are foreigners who can speak Chinese in nearly every country of the World, rates for this could be extremely expensive, probably as high as 5 Euro per comment. Even USA is not rich enough to afford that. If it is done by Chinese in Mainland China, how can they possibly get recruited? In a country with such strict controls it would be a risky thing to do.

I think 美分党 is just a name used by nationalists to counteract 五毛. It’s a game of exagerated name-calling. Same like in the West, in response to being called “nazis”, far-right activists their opponents “commies”.

I found an interesting article about the censorship on the Chinese internet. The article shows a list of words that are censored on Weibo. So when you write a blogpost on Weibo a computer system scans your post and afterwards sensitive words are marked and you have to approve or delete the words. This list points out that it’s not possible to write about political Incidents and Issues, such as Tibet or the Tiananmen accident.

Furthermore the article explain that President Xi Jinping continue to pursue cyberspace sovereignty’ as top priority. China was even voted as ‘the world’s worst abuser of internet freedom’in 2015. In my opinion this is a terrible case, because even though the government wants to secure their own safety without having protests or accidents, people should know their history and speek freely. Especially nowadays, because people get more chances to travel outside of China where they can search more freely and get new information. Afterwards they can spread these new insights in China. So I don’t think the government can continue their censorship strategy for a long time anymore.

This is the article I refer to in my comment above:

http://earp.in/en/capturing-the-growth-of-digital-nationalism-in-china-2/

I think the government’s policy will not change with regards a monolithic version of Chinese history. The fact that more Chinese people can go abroad and search more freely on the Internet is not affecting this government’s policy. The thing is that the government is concerned about what the majority of the people think about Chinese history, not about a limited number of people who can afford to go and study abroad. The government still allow a certain number of people to surf the net without almost any limitation. Nevertheless, it sets strict rules for the brader ‘masses’. This attitude also reflect the fact we discussed in class about being ‘digitally’ educated. If everyone can have access to all kinf of information the government cannot anticipate the overall reaction.

Three articles about a new movement online called “Little Pinks”. They are predominately young women, who believe that they have a sense of duty in supporting the chinese government against critics and negative news. This new online nationalism began In January, when Tsai Ing-wen, a Taiwanese politician who supports independence, was elected president.

http://chinadigitaltimes.net/2016/08/little-pinks-new-face-chinese-nationalism/

http://www.economist.com/news/china/21704853-online-mobs-get-rowdier-they-also-get-label-east-pink

http://foreignpolicy.com/2016/08/25/the-new-face-of-chinese-nationalism/