Digital Territories in East Asia

A Discussion with Students at Leiden University

Over the past three months, our grad students here in the Leiden Asian Studies programme have been debating the many ways in which digital technologies impacts politics, society, and culture in East Asian contexts. As we conclude our semester, I have asked them to come together for one last online debate, this time on digital territories.

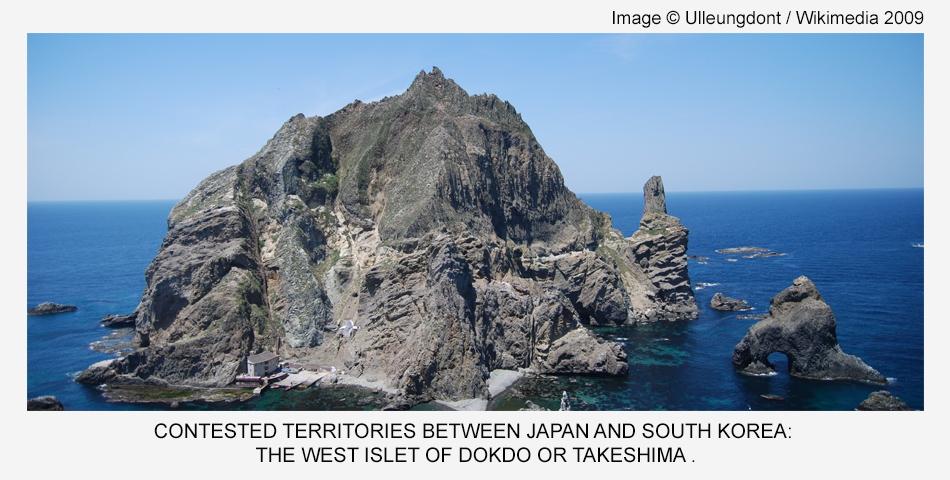

National territories are a matter of heated feelings in many places around the world, and the East Asian region is an illustrative place to turn to if we wish to understand how nationalism, sovereignty, and questions of territory work today. The legacies of war loom large in the region, and the history of WWII and the Cold War have left their mark on the protracted ways in which various states and their citizens make sense of ‘homelands’. For instance, islands in the East China Sea frequently become a matter of political dispute between the three states that claim sovereignty over the rocks: the People’s Republic of China, the State of Japan, and the Republic of China on Taiwan. To the north-east, Japan and Korea both lay claim to islets in the Sea of Japan, which are known as Dokdo in Korean and Takeshima in Japanese. Meanwhile, to the south, various countries are protesting what they perceive as aggressive moves by the PRC to consolidate its position in the South China Sea. These disputes can lead to diplomatic rows, public protest, high-profile activism, and even the risk of outright military conflict.

Territorial disputes are frequently analysed and interpreted within frameworks of realpolitik, that is: through theories that highlight the competition between states over limited geopolitical resources. And yet the political meaning of ‘territory’ is heavily constructed through communication practices, beliefs, and worldviews. ‘Traditional’ types of media play an important role in this, for instance museums, maps and passports, and textbooks. Increasingly, however, knowledge of what counts as national territory is created, presented, filtered, and consumed through digital technologies (Schneider, forthcoming). Considering the ongoing debates about the ways in which public opinion and foreign policies might be connected (cf. Gries et al. 2016), it seems prudent to ask what role physical and digital territories play in dynamic political context like those in East Asia.

Where do ‘territories’ exist, what are they, and who is in a position to shape their meanings? What roles do technologies such as search engines, wikis, web portals, mobile phones, apps, and video games play in conjuring up or presenting specific versions of national sovereignty? How can we study these phenomena, and what conclusions should we draw from East Asian examples about the connection between digital technology and politics? And finally: how might insights from media and communication studies connect with more mainstream approaches in the study of international relations as observers try to make sense of ongoing territorial disputes? Join us in the comment section below to share your ideas and any interesting resources that might shed light on this crucial dimension of international relations and communication.

References

Gries, Peter, Steiger, Derek, & Wang, Tao (2016), ‘Social Media, Nationalist Protests, and China’s Japan Policy: The Diaoyu Islands Controversy, 2012-13’. In De Lisle, Jacques, Goldstein, Avery, & Yang, Guobin (eds), The Internet, Social Meida, and a Changing China. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press (pp. 161-179).

Schneider, Florian (forthcoming), China’s Digital Natioanlism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Share This Post, Choose Your Platform!

71 Comments

Comments are closed.

I am usually all for viewing politics, including disputes over sovereignty, as being downstream from culture. I am less sure if this also works when applied to territories such as Dokdo/Takeshima since those are uninhabited and therefore do not have a culture. This is what makes that dispute (and the Senkaku/Diaoyutai) different from similar disputes over Taiwan, as well as the Falkland Islands/Malvinas and, for a continental example, Macedonia.

In the case of Taiwan, culture is certainly a major point of contention in its sovereignty dispute. One surprising example of this is how the New Power Party, the most explicitly pro-independence party in the Legislative Yuan, embraces multiculturalism. The party endorses a ‘Taiwanese culture priority principle’ as well as ‘open multiculturalism’. To me, this embrace of a Taiwanese multiculturalism seems to be away to disassociate Taiwan from Chinese conceptions of nationhood.

Source: https://www.newpowerparty.tw/policy/%E9%96%8B%E6%94%BE%E7%9A%84%E5%A4%9A%E5%85%83%E6%96%87%E5%8C%96 (in traditional Chinese)

The party also hosts events specifically targeted at ‘new residents’ (新住民): http://mpark.news/2017/11/09/3531/ (in traditional Chinese)

To paraphrase Yih-Jye Hwang, few Taiwanese would consider Thai immigrants to be a part of the Taiwanese nation. That just might be changing. And counterintuitive as it might seem, we very well might have a nationalist movement to thank for that.

What I am going to say might be a bit far away from the topic of “digital territory” but I am interested in what you said about “Thai” immigrants since I worked in Thailand on this topic before. Would you please kindly give the reference where Yih-Jye Hwang says that?

I think it might be simplified if we say “few Taiwanese views Thai immigrants as part of the Taiwan Nation”. After the civil war between kuomintang and CCP, some troops of Kuomintang escaped to Burma and Thailand, and live there till now. It is said 1/10 of Taiwan overseas funding is distributed to Thailand. The government also sends military volunteers to Thailand to teach Taiwanese. As what I observed, Han-Taiwanese has no problem accepting them as Taiwanese but Taiwanese aborigines consider it as “the Taiwanese government is trying to colonize Thailand as what they did with Taiwan.”

Here is the full in-context quote:

‘Very few so-called liberalists in Taiwan can easily get rid of the shadow of essentialist/nationalist ways of thinking considering what constitutes a nation, since they all face a theoretical and practical predicament: how to decide who “the people” are in the first place. Or, who is eligible to be granted civic rights if citizenship is the cornerstone of nation building? In other words, what does it mean to be a “civic” nation-state without being able to decide whether one is part of another national community, or legally, as well as civically separate and distinct? Very few people in Taiwan can accept, for instance, that a Thai laborer in Taiwan would become a member of a “Taiwanese nation”‘ (p75-76).

I think it is safe to say that the Thai laborer in this quote can be replaced with a laborer from any Southeast-Asian country.

Source:

Hwang, Yih-Jye, ‘Historical and political knowledge in the discursive construction of Taiwanese national identity’ in: Liu, Joyce C.H and Nick Vaughan-Williams, European-East Asian Borders in Translation (New York 2014), 63-78.

Thanks! If he is talking about the Thai labors, then I think this argument is solid. I was a bit confused about what he meant by the “Thai” immigrants and thought it may cover the Thai residents who consider themselves Taiwanese.

I’m not sure to what extent it is rightful to say Dokdo-Takeshima does not have a culture because it’s an unhabited place. I do think that Dokdo-Takeshima can be part of culture as a community (such as Korea and Japan) are able to give meaning to the island themselves and therefore give it a certain load of cultural relevance.

I think that is obvious that island communities themselves are able to shape their own culture and history. However, most of the time I think this process of meaning creation could be considered the direct consequence of the islanders’ resistance against hegemonic powers. To quote an example, if we take the strong cultural isolation of Corsican it becomes clear that this feature has been harshly exacerbated by the protracted undesired imperialist domination.

As for the Diaoyu islands, the political dispute is often mentioned. Even this year, there happens quite a lot, but without actual development. https://www.google.nl/amp/s/amp.theguardian.com/world/2017/feb/05/china-v-japan-new-global-flashpoint-senkaku-islands-ishigaki

The Senkaku Islands dispute is an interesting one. Doctor Wakefield and the article below explain that according to international law, the islands are Japan’s property. Even though Japan has offered to go the International Court of Justice in Den Haag, China refuses to do this. Therefore from my perspective, the dispute should have been over a long time ago.

http://opil.ouplaw.com/view/10.1093/law:epil/9780199231690/law-9780199231690-e2015

Could you elaborate on why you think the dispute should have been over a long time ago? Is that only because China refused to let the ICJ decide on that case?

Related to this, the article below from The Diplomat argues that China is very attached to Westphalian assumptions. The Peace of Westphalia in 1648 led to a world system of independent and sovereign states that later interacted through international law. Do you think this is credible whilst keeping China’s territorial conflicts in mind? Or is it possible that East Asian states (particularly China) are increasingly reshaping the world into an ‘Eastphalian’ world order, as the second article discusses (and therefore not necessarily recognizing the jurisdiction of the ICJ or other international tribunals)?

https://thediplomat.com/2014/05/chinas-westphalian-attachment/

https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=1409&context=ijgls

Hmmm, bear in mind that while the treaty of Westphalia promised sovereignty, this sovereignty was not extended to the colonies. The right to self-govern was later also vehemently defended by the “Third World” & in particular the “Non Alignment Movement” during the Cold War (check out any of Nehru’s speeches on the NAM). This was clearly not the case for the Europeans (& Americans) that were the supposed protectors of every country’s right to sovereignty.

Western-centrism & privileging in international relations & international law is a bit of a minefield actually. But I don’t think the Diplomat article does a very good job at navigating this minefield. Simply the claim the ‘the world is moving on from a Westphalian system’ because it recognises individual actors that drive state decisions and then moving to criticising China’s emphasis on sovereignty stands a bit on weak ground… Panda seems to imply that ‘the world’ (& particular ‘the West) has accepted that sovereignty is not possible, because that is what he is pointing out in China’s international behaviour. Last time I checked, no country is happy with other countries intervening in their state? Overall the article is quite reductive & suggestive (maybe even accusatory?) of Chinese foreign policy.

As for the ICJ & the ICC, they tend to be mired in controversies & have had to deal with many accusations of Western bias. The Nicaragua vs. the U.S. case for instance in which the U.S. rejected the judgment by the ICJ after it lost the case. The ICC has historically faced criticism from many African states, along with China, which has led some to proclaim their intentions to withdraw.

Anyways, what were your opinions on the articles? Also, do you think China is shaping an ‘Eastphalian’ order or no?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Court_of_Justice#Criticisms

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nicaragua_v._United_States

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Criminal_Court#Criticisms

https://gadebate.un.org/en/68/ethiopia

(sorry for the Wikipedia spam, but just the easiest place for a comprehensive overview of criticisms)

Linking to what Ales stated, I’d like to stick with Nationalism in the digital space. A milestone of the cyber-nationalization process burst by CCP is Xi Jinping’s Wuzhen Declaration in which the President introduced the importance of internet sovereignty as the bulwark of every single nation and their inherent differences

http://www.wuzhenwic.org/2016-11/18/c_61834.htm

What I find very interesting, but which does not concern the digital sphere, is the Economic Partnership Agreement which was signed between Japan and Indonesia in 2008, and apart from free trade and infrastructure investments, also involves the strengthening of maritime ties between the two countries. What the news article below already mentions, but I also strongly believe, is that this agreement is used as much more than just to foster economic growth for Indonesia, but that is is especially a political tool for Japan to form a front against China in the island debate, by securing the bonds with their (island state) allies and making sure they agree on maritime and military cooperation. Therefore, the issue is far from over, as Japan believes they need to ‘suit up’ in order to fend off China.

https://www.usnews.com/news/business/articles/2017-01-15/indonesia-japan-affirm-deeper-ties-during-abes-asian-tour

While the debate is still very much a political hotbed, with the eventual ‘symbolic’ outcome (if there ever will be one) will be an end to this ongoing power play(and nothing more) between two nations, ordinary Japanese citizens are growing more and more ambivalent about the issue, to the extent they simply do not care. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2017/10/28/national/politics-diplomacy/japanese-less-interested-senkaku-islands-takeshima-islets-government-surveys-show/#.WjEQdd_ibIU

I have often questioned the actual effectiveness of online and offline protests in China lately, particularly the 2012 anti-Japanese protests and the 2016 anti-US protests. Apparently, not only they look bigger than what they actually are. This article on China Digital Times argues that many citizens find such protests annoying and counterproductive, and in certain occasions even try to contrast them.

https://chinadigitaltimes.net/2016/09/backlash-online-chinese-nationalism/

About the 2012 anti-Japanese protests, it might be the case that citizens find such protests counterproductive, but that is only one side out of dozens. For example, the article linked below argues that it had significant disruption on trade and investment flows, between Japan and China. So while it might not have been a way of getting everyone in a nationalist spirit, it certainly had an economic impact.

https://iapsdialogue.org/2017/10/25/bad-blood-effects-of-the-2012-anti-japanese-protests/

There might be a difference between China and Japan here though as the traditional information supply in China is a bit more ‘suggestive’. This would be in line with Denemarks argument in this weeks reading in which he states that the traditional media which “virtually every Chinese” uses predominates online (extreme) nationalism.

What do you guys think?

Oops, misread your comment, Steef.

Still it is very interesting to look at why the 2012 anti-japan demonstrations derogate from Denemark’s/Andrea’s argumentation and fit in to the example presented in the article bij Gries et. al where successful online nationalism even plays “a critical role in escalating the Chinese party-state’s response”.

What are the (pre)conditions for online nationalism to be influential?

This reminds me of a post I saw on my Wechat Moments when I lived in China in 2014. A woman I had met in Hunan apparently was rather anti-Japanese and posted messages in which she urged her Wechat friends to boycott Japanese products. During that same trip in Hunan I once walked past a restaurant that had geese standing in front of the entrance with a cardboard sign hanging through their neck that said ‘Long live China’, as well as a sign below the menu that said ‘Japanese are not welcome in this restaurant’. Such sentiments might be effective in that Japanese businesses and people are kept out, but it seems that the countereffects are often overlooked (e.g. no Japanese customers = less customers = less profit).

See this link for an example of an advertising goose: https://www.shutterstock.com/image-photo/fenghuang-china-live-white-goose-outside-575947201?src=3Yqa5gD7CAeydOrcq8F94g-1-0

And see here for examples of the anti-Japanese signage:

https://tieba.baidu.com/p/1471032728?red_tag=0306047233

Are there really so much Japanese in the area that not letting them in would hurt the business? On top of that, while such signs keeps Japanese costumers out, it very well might attract a certain kind of costumer as well by capitalising on their anti-Japanese sentiment. I could say the same thing about Japanese businesses that do not allow any foreigners. Doing that also attracts a certain kind of costumer. That more or less compensates the countereffect.

(This post is not an endorsement of such businesses/practices)

I agree with S.V. I don’t think there are so many Japanese in the area to make it counterproductive. However, this is one of the many contradictions I have seen in China. I remember eating at a Cultural Revolution themed restaurant in Heilongjiang where the waiters were wearing army uniforms, shouting slogans out loud aaand…..taking orders with apple iPads.

Cyber-nationalism is still very prevalent in Japanese society today, even though it is just a small part of the population taking part in it, these exclusive online communities also have the power to mobilize the people on- and offline.

https://www.nippon.com/en/currents/d00208/

Exactly. These nationalists are also quite powerful according the article linked below. The problem of these nationalists are that they are able to function in an almost complete anonymous environment. Creating a youtube video where you bash Koreans is not so powerful on itself, but when it goes viral, problems arise.

I also have reasons to believe that the revisionist and nationalist Prime Minister of Japan, Abe Shinzo, is using these people to his own advantage. Creating a narrative of nationalism is exactly what he wants, and if cybernationalists who possess immense power are able to help him, I would not be surprised if he leaks documents or anything similar to the big voices of those groups.

http://apjjf.org/2011/9/10/Rumi-SAKAMOTO/3497/article.html

I certainly think there is truth to that statement concerning the PM of Japan, while there won’t be any clear evidence he did so, his stance in certain political issues are certainly problematic and show his obvious lean to the right side: http://apjjf.org/2013/11/8/Tessa-Morris-Suzuki/3902/article.html

This article also shows (through a nice timeline) that despite the possible international scrutiny, Abe has never shied away from indirectly supporting the nationalists thoughts in Japanese society, and thereby upholding them at the same time.

http://apjjf.org/2013/11/1/Narusawa-Muneo/3879/article.html

Back in 2013 a game developer from Shanghai together with the People’s Liberation Army released an online game that allowed players to fight along Chinese troops to conquer the Diaoyu / Senkaku islands from the Japanese.

No idea how the game was received by the Chinese public and what the reasons for playing the game were (perhaps some people just wanted to try out a new shooting game without really caring about the background story). Still, I think it shows well how popular media such as games are used to at least imply ideas regarding national territories.

https://www.voanews.com/a/chinese-video-game-lets-players-seize-japancontrolled-islands/1715532.html

For a trailer of the game, see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LdpSgEn73ms&noredirect=1

The article below is also an interesting read. After the rule of the South Chinese Sea has been given to the Phillipines by the Permanent Court of Arbitration, Chinese idols used their social media accounts to show disagreement with this judgment. Subsequently, Vietnamese fans of these Chinese idols started to turn against them for nationalistic reasons, as Vietnam was also in the running to claiming the South Chinese Sea. The author begins his article with: ‘War has started over the South Chinese Sea – online.’, a sentence that shows how vivid these discussions can be held on the internet.

https://thediplomat.com/2016/07/the-social-media-war-over-the-south-china-sea/

What happens in Vietnam reminds me of Chinese fans’ behavior during the Thaad missile event. Chinese fans announce “there is no idol in front of the nation” and resist the “allure” of Korean idols.

http://www.tnp.sg/news/world/chinese-fans-boycott-k-pop-idols-over-missile-issue

Interesting case! It made me think of this situation from last year, where a Taiwanese K-pop singer waved a Taiwanese flag on Korean television, and was forced to apologize by her agency in a video where she sais ‘there is only one china’. Here you see that an idol is punished for communicating a nationalist message during election time, which seems to have had the effect; because she looks pitifully forced in her apology video she garnered lots of support from Taiwanese online users and I think from Chinese online users as well.

I think online users in (East Asian) countries can change from supporting to turning on an idol or celebrity pretty quickly. Do you agree, and what do you think of the massively support or rejection of celebrity’s actions as a political statement itself?

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2016/01/16/watch-teenage-pop-stars-humiliating-apology-to-china-for-waving-taiwan-flag/?utm_term=.49cdb3773522

I have to say that I agree depending on who the celebrity is, to be completely honest. In the case of TWICE’s Tzuyu, it felt disproportionate to turn a spur-of-the-moment thing of a 16-year-old girl in a clearly non-political profession with no political motives (as political motives are quite funest for her line of work) into a political drama and make her a symbol in an ongoing, larger dispute. My disagreement with the issue is completely contextual.

I feel like the massive support and rejection is warranted when a celebrity’s actions are clearly politically motivated, as that is the purpose of the action. Like, I find the move of the PRC to block South Korean content over the THAAD issue a strategically smart one, as it is a punch that South Korea definitely felt, but I’ve also felt that the celebrities featuring in the media blocked in the issue have been unfairly targeted despite having no real political motivations.

I agree as well! According to the article below a lot of similar events happened during that year.

https://www.whatsonweibo.com/another-apology-to-china-anger-displays-nationalism-on-chinese-social-media/

I was thinking of this girl as well. But I thought she in fact lost fans from both Taiwan and mainland China. Mainland China people believed the girl only apologized to maintain her fan group while the Taiwanese felt betrayed (Tzuyu is Taiwanese). I think supporting or rejecting an idol makes it easier for the ordinary to have a political statement. Sometimes expressing one’s opinion towards a celebrity becomes “political correctness”.

I wonder to what extent this is part a CCP strategy though (as the article suggests). Especially since the article by Denemark and Chubb argues that the traditional media are by far the strongest in terms of the ‘creation’ of government support, the hint towards this acerbic nationalism as something private.

Any clue?

http://www-tandfonline-com.ezproxy.leidenuniv.nl:2048/doi/pdf/10.1080/1369118X.2015.1093527?needAccess=true

Joost, I am curious how you would understand the following article:

https://www.whatsonweibo.com/support-chinas-new-era-campaign-goes-viral-chinese-social-media/

This definitely hinges towards propaganda. Still I think its very hard to distinquish extreme opinions from party-led propaganda in other cases. Wouldn’t the debate around #ad #paidpartnership on instagram come in handy here ;)

Perhaps, as the new career of ‘influencer’ is emerging, companies and even the government could be making use of the massive amount of people that famous stars can reach. As you mentioned, the hashtags #advertisement are showing up more and more. Now I can imagine the government not wanting to have the political statements by famous stars being marked as #advertisement, so to me it’s quite difficult to pinpoint motivations

https://www.ft.com/content/2de5b336-4a89-11e7-a3f4-c742b9791d43

Though the “map” is a traditional form of media in the shaping of national territory, the digital map might be the product of the new generation. Digital maps made in different countries can not only show how the country assumes its territory to be (including certain island or not, for instance) but also how it expects to control its domain. The link here claims that the digital cartography is under the control of Chinese government. Apple or Google maps do not show the real geography of China.

http://www.travelandleisure.com/articles/digital-maps-skewed-china

The link is here. Or you can click my name above for the hyperlink.

https://www.computerworld.com/article/2485454/enterprise-applications/taiwan-protests-apple-maps-that-show-island-as-province-of-china.html

Another case of people are sensitive to the territory showed on digital maps. Taiwanese get upset when Apple Map shows Taiwan Island as a province of China and demand Apple to change it. How to name “Taiwan” is always a controversial issue whenever a map illustrating East Asia is needed.

It is a sensitive subject indeed. But I was shocked to see that even Wikipedia points to Taiwan as China’s province: “Taiwan Province is one of the two administrative divisions of the Republic of China (ROC) that are officially referred to as “provinces”.”

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taiwan_Province

Hmmm no…ROC is the official name of Taiwan..PRC is the government of mainland China. :) So wikipedia in fact supports the independence of Taiwan as a country.

I wonder how many times Chinese bots and hackers have tried changing ROC to PRC. It comes back right at what Dr. Schneider talked about when we discussed Wikipedia. How neutral can it be, and in cases like this, does it need to take a decision, or can it just list the two options (either ROC or PRC) under “contested” or something similar.

That page is about a somewhat obsolete layer of government, and its territory does not even contain half of the Taiwanese population.

As for the ROC being the official name for Taiwan, that works on some level, but there are reasons not to conflate the two. Consider, for example, the controversy about whether Taiwanese history textbooks should present between 1895-1945 from a ROC perspective (which would mean excluding Japanese-ruled Taiwan) or a Taiwanese perspective. Taiwanese nationalists are also the ones who want to get rid of Chiang Kai-shek statues and other symbols of the ROC. Conflating Taiwan and the ROC might suggest otherwise and therefore be somewhat confusing.

Wikipedia actually has three pages on Taiwan:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taiwan

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taiwan_Province,_People's_Republic_of_China

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taiwan_Province

Each page uses a different POV in accordance to which government claims to ‘own’ the island. The talk pages are definitely worth to check!

The makers of digital Maps must be experiencing difficulties bordering China as a whole (not only Taiwan). See the next link to the disputed territories on the China-India border.

http://edition.cnn.com/2017/07/19/asia/india-china-border-standoff/index.html

The border dispute between China and Tajikistan should have been solved in 2011, but still remains as a dotted line on Google Maps.

http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-pacific-12180567

Also, the China-Pakistan border is drawn as a dotted line on Google Maps. Is this because of the non-recognition of India?

https://www.forbes.com/sites/ralphjennings/2017/07/27/chinas-3-worst-border-disputes-and-its-best-border-buddy/#3459356a4f36

(see bottom of the article)

It’s interesting to see the dotted lines representing claimed borders on maps instead of just showing enforced or, dare I say, ‘actual’ borders. I wonder which option would spur on border conflict more. Is it naïve to think that showing both claimed borders would keep someone from dogmatically thinking that one border is the true border?

Those maps certainly have their effect. It seems quite common for Chinese arguing in online comment sections to be totally baffled by anything that does not line up with the territorial claims of the PRC government. Think of comments such as ‘you know nothing of geography!’ or ‘just look at a map of China!’ in response to discussions of sovereignty over Taiwan and the South China sea.

Then again, maybe such comments are just strawmen. Dismissing someone as being ignorant of the map of China is a lot easier than responding to what they are actually saying.

Yes, symbolic can raise a Chinese nationalist’s anger very easily, like “wrong” maps, flags, and certain clothes. Last year SVS (the Leiden sinology students union) designed a poster with Chinese map on it. I noticed the first thing the Chinese (both mainland and Taiwan) students looked at, was if Taiwan was there. Ironically the map did have Taiwan but missed Hainan. But the anecdote shows how this politic sensitiveness of territory is rooted in mainland Chinese.

ROC might be the official title of Taiwain, but it is still referred to as “Taiwan province”.

I am sorry but I don’t get your point. The province is the administrative division of both PRC and ROC. It is natural that it is referred as Taiwan province…..So I think being referred to as “taiwan province” cannot show if the writer supports its independence or not.

The Republic of China governs more islands than just the island of Taiwan, so it makes sense to refer to that island as ‘Taiwan province’.

It is interesting that you bring up this issue, because it is true that Apple and Google Maps do not show the real geography of China, or in fact any place in the world. As many will know, the Mercator projection which these digital maps use is by no means an accurate display of what the world looks like. By now, the Mercator projection is already somewhat outdated, as it has been criticized for being eurocentric (the projection enlarges the size of Europe, North America and Northern Asia) for a while now http://www.businessinsider.com/mercator-projection-v-gall-peters-projection-2013-12?international=true&r=US&IR=T. It is interesting that Google and other companies still choose for the Mercator projection in their digital maps.

They still use the Mercator model because whatever model they would use, the article below argues that the problem is: “it’s impossible to stretch the 3D sphere shape of the Earth onto a 2D sheet of paper. No matter which way it’s done, there will always be a compromise somewhere on shape, size, direction, distance or scale”.

Even if they would use the Gall-Peters style map, it would be distorted as well. Furthermore, changing up the notion of how the earth looks like could scare away potential costumers as they are not used to it. If the competitor would use the ‘normal’ style maps, they might use those services over, for example, Google.

https://www.businessinsider.nl/boston-school-gall-peters-map-also-wrong-mercator-2017-3/?international=true&r=UK

The great thing about digital technology, however, is that we do not need to work with a 2D sheet of paper. For example, Google Earth is an actual globe and it seems to work absolutely fine, why not use Maps in this way? There surely must be a reason for it, and I think your second argument sounds very interesting.

Speaking of maps, this article gives some insight into the ways in which maps are increasingly being used to arouse nationalist sentiments in East Asia.

https://antipodefoundation.org/2013/05/14/intervention-cartographic-nationalism/

This website is completely contributed to East Asia’s geography, including political and economic divisions.

http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/geography/element_d/ed13.html

I am not the first one to point out the relation between gaming and nationalism, but I find it interesting how in an internationally connected environment such as online gaming communities, nationalism plays such a large role. This indicates once more that globalization/ a more internationally connected world does not usher in the end of nationalism or national borders, be they offline or ornline, per se.

http://www.scmp.com/culture/arts-entertainment/article/2117091/nationalism-xenophobia-and-racism-online-games-unchecked

I wonder if these nationalistic conflicts are being intensified by the increased contact between nationalists of different countries, or if these conflicts are just more visible because of the internet (but not being intensified).

My first thought is to your comment is that the nationalist conflicts that you’re talking about are being intensified and more visible, because the internet makes increased contact between nationalists of different countries/provinces/ areas possible. In history political ideas like communism or the ideals of the french revolution were spread across countries, could it be that nationalists of different countries had contact with each other there and exchanged ideas? In that logic, could increased contact between nationalists of different countries make nationalist conflicts more intense? I think so.

I looked on wikipedia if there was anything on the spreading of nationalist ideas across countries, here is a link if you’re interested: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rise_of_nationalism_in_Europe

I also think that, because online users don’t directly see the emotional reactions and repercussions of the messages they write it’s easy to get spurred on and swept up by the tone of discussion that they see online, because the emotional reactions and repercussions of extreme comments aren’t visible to the writer. This could mean that conflicts are or seem more intense on the internet whereas they wouldn’t be as dramatic if we had the discussion in real life.

The question is, do online conflicts escalate to (more intense) conflicts in real life?

I think whether online conflicts can escalate to conflicts in real life heavily depends on the context and participants of the conflict. It also depends on whether the words can be converted into successful actions. As an example I’m taking the right-wing forum “Ilbe” in Korea, which is known to be somewhat of a breeding ground for nationalist hatred towards anything deemed un-korean. Whilst their online discourse is intense and worrying, the actions they have taken to, such as having dinner-parties in front of grieving parents on hunger-strikes, have only been met with scorn from the public because of who were participating (young males). The fact that there was an online breeding-ground for these nationalistic right-wing sentiments to grow and nurture each other did increase their intensity, but I wouldn’t say that the offline consequences of them are necessarily more intense or dangerous. It really depends on who, what and where, in my opinion.

http://english.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition/e_national/654589.html

Also I think that any movement sparks a counter-movement, so to see nationalism rise in the face of growing connectivity and globalization is something natural. It’s just that due to the increased connectivity, this growing nationalism has an opportunity to spread to others with increased sentiments, leading to e.g. groups like Ilbe.

This story contrasts with the Denemark article quite a bit: FT argues that China has difficulties controlling online nationalism which creates ‘uncertainty’. In that case Denemark and Chubb might be underestimating the power (whereas Gries et. al. recognise that it plays a critical role in the CCP’s agenda)?

https://www.ft.com/content/5ae7b358-ce3c-11e6-864f-20dcb35cede2

Important here is the ability to ‘control’ nationalism. Not sure where I read it, but I believe either Gries (2004) or Callahan (2013) discusses the issue with ‘correct’ and ‘incorrect’ outpourings of nationalism. The problem with the Internet is that it allows for online discussions & people with more extreme view to find each other, outside of the control of the party. This would still follow Denemark & Chubb findings that those who follow mainstream media have a more favourable few of the party. It would also still hold true for Gries et al. that ‘popular’ nationalism plays an important role for the part, but more in a way that they would need to channel that energy in ways that are pro-party and don’t make the CCP seem weak/bad/ineffective.

Callahan, William A. (2013). China Dreams. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gries, Peter H. (2004). China’s New Nationalism. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Even though I won’t claim who has rightful ‘’ownership’’ of Dokdo-Takeshima, I do think that Korea has the most rightful claim considering multiple factors. I do not necessarily think this Dokdo-Takeshima issue has got to do with territory, but more with identity. From my point of view Dokdo-Takeshima kind of functions as some sort of metaphor of deeper underlying issues (on levels of identity, culture and the colonial past) in which Dokdo becomes the embodiment of. Therefore, I often find it saddening to read how many consider it just a ‘’collection of rocks’’ and ridicule it.

Relevant links:

https://cpianalysis.org/2014/10/13/koreas-dokdo-claim-is-about-more-than-just-territory-its-identity/

http://www.dokdo-takeshima.com/why-japan-cant-have-dokdo-ii.html

Also, in the eye online activism, there exist numerous forums, (online) institutes and social media pages to spread the word on Dokdo-Takeshima belonging to Korea (some of the following links are even part of government departments).

Relevant links:

https://www.facebook.com/독도지킴이-세계연합-1529679140676770/

http://vank.prkorea.com/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0_RPpTxVM1A

http://dokdo.mofa.go.kr/m/kor/

http://www.dokdohistory.com/eng/gnb02/sub01.do?mode=view&page=&cid=47323

What I have taken away from the discussion on territorial disputes in Asia (but also in general) is that, while these disputes may be about resources on a political level, on a personal level they’re often concerned with differing realities. In one person’s reality this specific island belongs to X, but according to that person’s reality, this island belongs to Y. There’s no easy solution, as dividing a territory would leave both parties unhappy and still wanting the half they didn’t get. Even though people might have zero intention of moving to said territory.

You see this in video games as well. Here is an example of Chinese gamers becoming angry because Taiwan wasn’t shown on the map when selecting the People’s republic of China.

https://www.taiwannews.com.tw/en/news/3057143

The map shown didn’t match the reality these gamers had in mind, so they got mad. I do think that the only way to get people to be mad about these differing realities is to keep showing differing realities to people, as then they might accept differing realities and change their own. This is difficult because of the vested political interests at the national level, as these realities get constructed through (digital) media and education which are controlled or strongly influenced by governments.

Anyone any thoughts?

The Chinese government did ban a game that depicted Taiwan, HK, Macau, and Tibet as independent countries back in 2004, citing that it would “pose harm to the country’s sovereignty and territorial integrity”. So, this definitely shows the vested political interests in portraying the Chinese territory in one specific way.

http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/english/doc/2004-12/08/content_398445.htm

Overall I do think you are right, especially in highlighting the importance of emotions in nationalism. And, while I do agree with the influence of education and its control by the government, I don’t think media, digital or not, necessarily has the power to change people’s minds. For instance, Japan’s, Taiwan’s, HK’s, the Philippines’ etc. online media are not controlled to the extent that the Chinese Internet is controlled, but when it comes to territorial disputes nationalism nevertheless plays an important role. I’d say the confirmation bias plays a much more important role due to the emotional stakes in the disputes. What do you think?

You’re right, I think I overstated the influence any non-Chinese government might have on a nation’s (digital) media (at least to the extent that it can put an end to these territorial disputes on a personal level.

Are there any other options then?

That is an interesting question. I think people are not easily convinced when they see different opinions, especially when it is about a topic such as nationalism. The online outrage is not about the islands themselves, but about national identity. When the topic is so closely linked to national identity, I think people will not easily change their minds.

The government sometimes uses these nationalist views for its own agenda. However, I wonder to what extent an online nationalist discourse is within the control of the government. In other words, can a nationalist online movement get out of hand? I think it can: the government might support or even instigate a certain movement, but it is unclear how this movement proceeds.

An example is the boycot Japanese products movement. The government benefits from this movement, but I strongly doubt if the government envisioned a movement in which Japanese cars owned by Chinese were destroyed. On top of that, Chinese salesmen who sell Japanese cars, had a difficult time, as illustrated in this article: http://www.businessinsider.com/chinese-boycott-hurts-japan-2012-9?international=true&r=US&IR=T

My answer to your answer is yes: even though is mostly the government which gives momentum to nationalist online movement, other entities could at a certain point commit to foment certain trend. These entities are generally known in China as 河蟹, namely “River Crabs”. This peculiar definition derives from the homophony of the term with the word “harmony”, which has been quoted as the main reason for PRC internet censorship. They are usually blogger with thousands of follower who support the government nationalist movements.

The economist deals with the boycott against South Korean products caused by the South Korean firm, Lotte, which allowed America to build an anti-missile base on the company’s territory. This article particularly shed a light on the influence of Chinese cyber nationalist.

https://www.economist.com/news/china/21718876-it-wary-going-too-far-china-whipping-up-public-anger-against-south-korea

The first thing that sprung to my mind when thinking about digital technology and national sovereignty is the way the South Korean government is not allowing foreign services such as Google to actually map their country effectively. Boyu mentioned it earlier in the context of China where maps sometimes do not show the actual China. It’s the same for South Korea where especially Google and Apple are prevented from taking high-quality data-images and are forced to store whatever data they have on servers within the South Korean territory. Foreigners used to the services of Google and Apple Maps have to switch to services by Naver Maps or Daum Maps in order to get around. This secures the consumer-base for these two South Korean services.

Source:

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/14/business/international/google-jousts-with-south-koreas-piecemeal-internet-rules.html

It would be interesting to analyze the digital discussion on the Doklam dispute, namely the contention of Bhutan sovereignty between India and China. Unfortunately, no academic effort has been spent yet on the topic.

Do have any idea to what extent the digital space could contribute to the rise of nationalism in this buffer state?

http://edition.cnn.com/2017/07/03/asia/bhutan-india-border-dispute/index.html

Looking at nationalism(s) in a different way would also be fruitful. So far, nothing has been said on for instance Uyghur nationalism or Tibetan nationalism. Xinjiang has had several instances where the Internet simply went offline during/after protests. Also, for both the Uyghur and Tibetans the transnational links that the Internet helps to sustain are extremely important for activism & nationalist movements

https://thediplomat.com/2014/07/how-china-dismantled-the-uyghur-internet/

http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14631369.2012.625711?journalCode=caet20

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-xinjiang-internet/china-tightens-web-screws-after-xinjiang-riot-idUSTRE5651K420090706